The KC Cultural EcoDistrict began not with data, models, or drawings, but with a gathering.

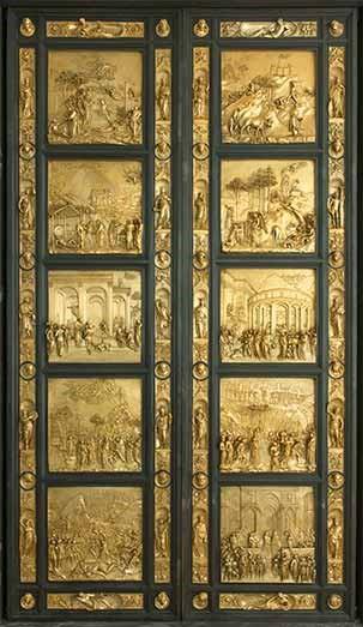

At the project kickoff, the interdisciplinary team assembled at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, standing together in front of the Gates of Paradise. The setting was deliberate. The doors, long associated with human achievement, craftsmanship, and cultural continuity, also carry a quieter legacy. During World War II, works like these became symbols of what could be lost forever, and of the extraordinary efforts taken to protect them. The Monuments Men and women, drawn from museums, libraries, universities, architecture, engineering, and the humanities, were tasked with emergency preservation under conditions of extreme uncertainty. They worked without the luxury of foresight, responding to crises as they unfolded.

FIGURE 1 – Gates of Paradise Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Like those wartime preservationists, the KC Cultural EcoDistrict team came from deeply overlapping professional backgrounds. Architects, engineers, conservators, librarians, facilities leaders, landscape experts, sustainability practitioners, and scholars all brought a shared commitment to stewardship. What differs today is the nature of the emergency and the opportunity before it.

Supported by a National Endowment for the Humanities Climate Smart grant, the project set out to ask a fundamental question: How do we protect culture, knowledge, and public life from climate risk before emergencies force our hand.

Climate change presents a slow moving but accelerating threat to cultural institutions. Unlike wartime destruction, its impacts arrive both through more frequent and more powerful storms as well as incremental degradation through heat, moisture, outages, and material fatigue. The damage is often invisible until it is cumulative. The difference now is that we are not limited to reaction. We have data. We have time horizons. We have the ability to plan. The KC Civic EcoDistrict was conceived as an act of foresight.

The work intentionally avoided prescriptive outcomes. Instead, it focused on building a shared method. The team evaluated buildings, landscapes, utilities, health and wellbeing, emergency readiness, and waste systems across two anchor institutions, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art and Linda Hall Library. The goal was not to create isolated recommendations, but to develop a repeatable framework that any cultural institution could use to understand risk, prioritize action, and coordinate with neighbors.

Cultural institutions are often stewards of irreplaceable collections, but they are also stewards of people, place, and public trust. Preservation today is not only about saving objects. It is about sustaining environments where learning, creativity, and civic life can continue under changing conditions. It is about shifting from heroic response to quiet preparation.

Standing in front of the Gates of Paradise, the project team reflected on the difference between emergency preservation and planned resilience. The Monuments Men and women acted with courage in the face of immediate loss. This project seeks to honor that legacy by acting earlier, more deliberately, and collectively.

The KC Cultural EcoDistrict represents a shift in mindset. It treats climate adaptation not as a future problem, but as a present responsibility. It frames resilience as an extension of preservation. And it recognizes that the most durable protection of the humanities comes not from reacting to crisis, but from designing systems, policies, and partnerships that prevent those crises from unfolding in the first place.

In that sense, this work is both a continuation of a historic mission and a new chapter. It is preservation with foresight, carried out not in secrecy or haste, but in the open, with time to plan for the emergencies of the future.