- Assessment of Existing Building Envelope

- Climate Risk & Environmental Footprint Considerations

- Facility Improvement Measures (FIMs) for Envelope Optimization

- Performance Modeling & Impact Analysis

- Implementation Strategy & Roadmap

Assessment of Existing Building Envelope

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

The assessment of the existing building envelope requires the identification and tracking of key performance indicators (KPIs) to ensure that data-driven decisions are made to optimize energy efficiency, durability, and environmental resiliency. These KPIs are categorized based on the primary performance metrics and material conditions that influence the envelope’s effectiveness.

TABLE 1 — Comprehensive Building Envelope KPI Table

| KPI Category | |

| 1. Energy & Carbon Performance | |

| Specific KPIs | |

| Heating Load Intensity (HLI) | U-value / R-value of walls, roofs, windows |

| Cooling Load Intensity (CLI) | Thermal Bridging Impact (%) |

| Peak Cooling/Heating Demand (kW) | Operational Carbon (annual mtCO₂e) |

| Envelope Air Leakage Rate (CFM @ 75 Pa / ACH50) | Embodied Carbon of Envelope Materials (kgCO₂e) |

| Infiltration Heat Loss/Gain (Btu/hr) | EUI (Energy Use Intensity) |

| Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC) impact | |

| 2. Durability & Resilience | |

| Specific KPIs | |

| Moisture Intrusion Rate / Moisture Content in Assemblies | Foundation Movement / Settlement Indicator |

| Freeze–Thaw Cycle Vulnerability Rating | Water-shedding Performance (parapets, flashing, etc.) |

| Sealant/Joint Failure Frequency | Wind Load & Impact Resilience Rating |

| Roof Membrane Condition Index (RCI) | Surface Degradation Index (cracking, spalling, efflorescence, UV wear) |

| Remaining Service Life (RSL) of envelope components | |

| 3. Climate Adaptation KPIs | |

| Specific KPIs | |

| Envelope Moisture Storage Capacity (especially mass walls) | Urban Heat Island Exposure Index |

| Rate of Drying Potential (per assembly) | Overheating Risk (hours above 80°F or 27°C) |

| Stormwater Absorption / Permeability at Perimeter | |

| 4. Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) | IEQ Thermal Comfort |

| Specific KPIs | |

| Temperature Stability in Perimeter Zones (°F variation) | |

| Mean Radiant Temperature (MRT) | |

| Thermal Gradient Across Windows/Walls | |

| Draft Rate at Envelope Interfaces | |

| IEQ Daylighting | |

| Specific KPIs | |

| Daylight Factor (DF%) | |

| Spatial Daylight Autonomy (sDA 300/50%) | |

| Annual Sunlight Exposure (ASE) | |

| Glare Index (DGP or UGR) | |

| Visible Light Transmittance (VLT) | |

| IEQ Moisture & Air Quality | |

| Specific KPIs | |

| Indoor Relative Humidity Variability in perimeter zones | |

| Condensation Frequency (glazing, frames, structural interfaces) | |

| Envelope Mold Growth Risk Index (ISO 13788 / WUFI) | |

| Pollutant Infiltration Rate (PM2.5, VOCs, ozone) | |

| Air Change Effectiveness (ACE) in perimeter rooms | |

| IEQ Acoustics | |

| Specific KPIs | |

| Outdoor-to-Indoor Noise Reduction (OITC / STC) | |

| 5. Water Management (Bulk Water + Moisture Control) | |

| Foundation Moisture Levels | Groundwater Infiltration Incidents |

| Roof Drainage Time to Clear Standing Water | Freeze–Thaw Damage Occurrences per Year |

| Rainscreen Ventilation Effectiveness | Bulk Water Penetration Rate (leaks, failures, testing) |

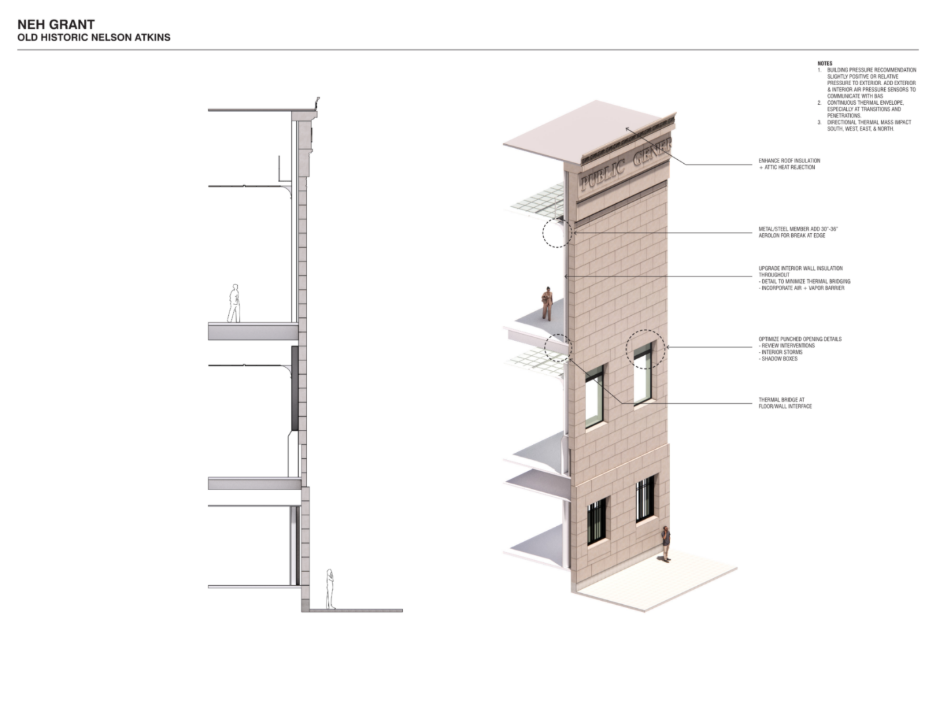

FIGURE 1 — Humanities Building with Heavyweight Structure

(Example: Nelson Building at Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Mo.)

Heavyweight Buildings (≥ 35 lb/ft² wall weight)

A heavyweight buildings are characterized by thick, massive envelope materials such as stone, multi-wythe brick, and concrete. These assemblies have very high thermal mass, meaning they absorb, store, and slowly release heat and moisture over long periods. This creates a stable indoor environment but also results in slow drying rates and delayed temperature response. Because of their mass and rigidity, heavyweight structures are inherently durable and resistant to many climate forces, but they can be vulnerable to deep moisture penetration, freeze–thaw cycles, and long-term material fatigue.

The Legacy Nelson Building exemplifies this type: its historic stone and masonry walls provide exceptional longevity and thermal inertia while requiring specialized preservation strategies to manage moisture, prevent cracking, and maintain envelope breathability. These buildings demand interventions that are minimally invasive, vapor-open, and compatible with heritage materials.

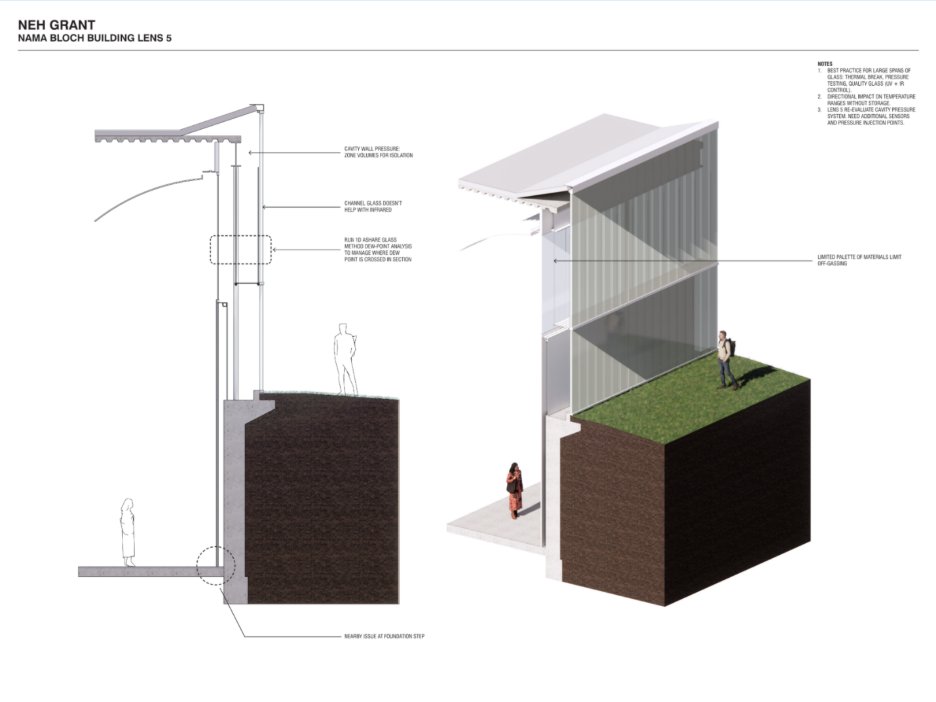

FIGURE 2 — Humanities Building with Lightweight Structure

(Example: Bloch Building at Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Mo.)

Lightweight Buildings (< 10 lb/ft² wall weight)

Lightweight buildings are composed of thin, low-mass envelope systems, often dominated by glass, metal framing, and other high-performance but low-inertia materials. With very little ability to store or buffer heat and moisture, lightweight structures respond quickly to outdoor temperature swings and solar exposure. This makes them highly vulnerable to overheating, rapid heat loss, condensation, and wind-driven rain infiltration, especially in climates with extreme variability.

The Bloch Building represents this condition: its iconic glass façade offers transparency and architectural lightness but requires precise control of solar heat gain, humidity, and air infiltration. Lightweight buildings benefit most from dynamic glazing, airtightness improvements, thermal breaks, and active HVAC coordination, as envelope performance is tightly linked to mechanical system behavior.

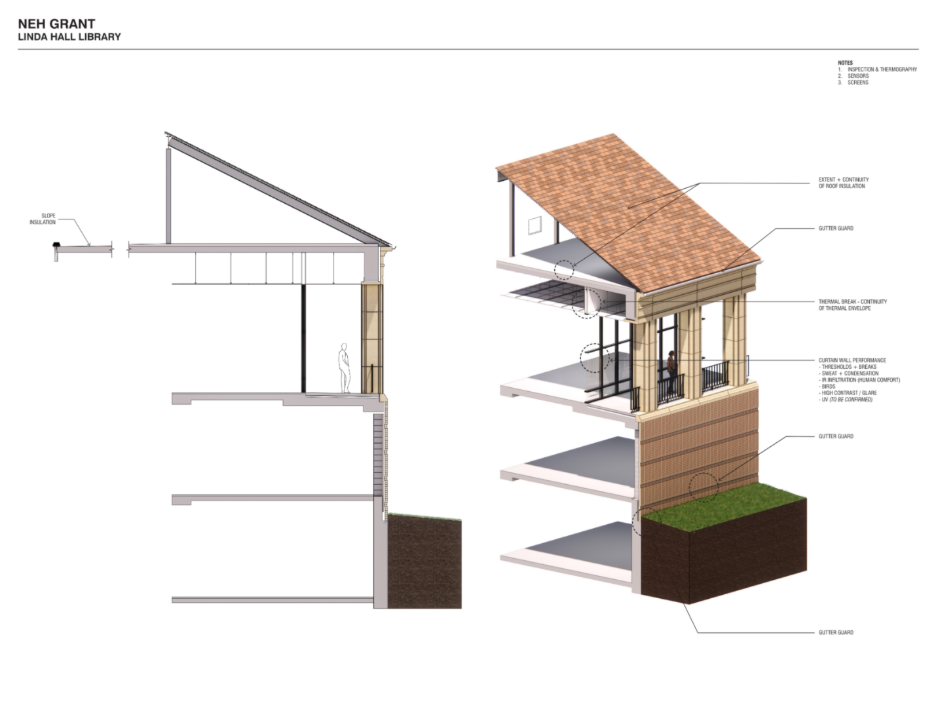

FIGURE 3 — Humanities Building with Mediumweight Structure

(Example: Linda Hall Library, Kansas City, Mo.)

Mediumweight Building (Between 10–35 lb/ft² wall weight)

A mediumweight building uses a combination of masonry, block, steel framing, and moderate-mass assemblies, offering a balance between the thermal inertia of heavy structures and the responsiveness of lightweight ones. These envelopes can buffer temperature swings better than lightweight buildings but still exhibit vulnerability to moisture accumulation within cavities, thermal bridging at steel connections, and freeze–thaw stress in brick and CMU.

Linda Hall Library exemplifies this hybrid condition. Its brick and block exterior provides durability and some thermal mass, while later additions and mixed-material assemblies introduce more complex hygrothermal behavior. Mediumweight buildings require strategies that emphasize moisture management, insulation compatibility, improved drainage, and thoughtful thermal-bridge mitigation, allowing them to leverage their inherent strengths while addressing their key vulnerabilities.

TABLE 2 — Humanities/Institutional Administrator KPI Framework

(“What We Evaluate”)

| KPI Category | What This KPI Includes (Plain-Language Description) |

| Thermal Performance of the Envelope | How well the walls, roof, windows, and foundation resist heat moving in and out of the building. Includes the building’s ability to maintain stable indoor temperatures and limit energy waste. |

| Air & Moisture Control | How effectively the building envelope keeps outside air and moisture from entering, and prevents indoor humidity from causing damage. Includes leakage around windows/doors and water penetration through walls or roofs. |

| Structural and Climate Resilience | How well the envelope stands up to climate-related stresses: heat waves, cold snaps, heavy rain, snow, wind, storm events, and freeze–thaw cycles. Includes durability and long-term stability of envelope components. |

| Indoor Environmental Stability (Envelope-Driven) | How the envelope influences interior comfort: temperature uniformity, humidity stability, and protection of sensitive collections. This KPI captures how well the envelope supports healthy, stable indoor conditions. |

| Material Lifespan & Condition | The long-term health of exterior walls, roofs, glazing, sealants, and foundations. Includes aging, deterioration, compatibility of historic materials, and risks that shorten useful life or create unexpected failure. |

| Climate & Carbon Impact (Envelope-Related) | How envelope performance affects energy use, long-term carbon footprint, and environmental impact. Includes operational carbon from HVAC demand and embodied carbon tied to envelope renovations. |

TABLE 3 — Technical KPI Definition Matrix

| KPI Category | What We Study Within This KPI (Technical Components) | |

| 1. Insulation & Thermal Resistance | ||

| Thermal mass effects (heat storage & release) | R-values & U-values of all envelope assemblies | |

| Thermal gradients across wall/roof assemblies | ||

| Locations and severity of thermal bridges | ||

| Interior surface temperatures relevant to condensation risk | ||

| 2. Air & Moisture Control | ||

| Continuity of air barrier layers | Air leakage pathways at doors, windows, joints | |

| Bulk water pathways at flashing, parapets, roof edges | ||

| Vapor permeability of assemblies (inward/outward drying potential) | ||

| Moisture storage vs. release characteristics of wall systems | ||

| 3. Structural Vulnerabilities to Climate Stressors | ||

| Sealant/connection weaknesses under thermal expansion | Envelope susceptibility to wind pressure, uplift, racking | |

| Freeze–thaw susceptibility of masonry or porous materials | ||

| Structural behavior of glazing systems under stress | ||

| Movement, cracking, displacement of envelope materials | ||

| 4. IEQ Impacts Related to Envelope | ||

| Humidity stability vs. envelope-driven moisture loads | Temperature uniformity in perimeter zones | |

| Condensation potential on framing/glazing surfaces | ||

| Radiant asymmetry near exterior walls | ||

| Envelope impact on pollutant infiltration | ||

| 5. Material Condition & Lifespan | ||

| Sealant and joint conditions | Aging and deterioration mechanisms (UV, moisture cycling, corrosion, spalling) | |

| Compatibility of historic and modern envelope materials | ||

| Projected remaining service life of components | ||

| Degradation patterns indicating system failure | ||

| 6. Environmental Footprint & Carbon Implications | ||

| Impact of envelope performance on peak loads | Energy loss attributable to envelope deficiencies | |

| Embodied carbon implications of envelope materials | ||

| Long-term operational carbon reduction potential of proposed upgrades | ||

| Lifecycle durability vs. replacement frequency | ||

Current Envelope Performance

The current performance of the building envelope is a critical factor in assessing its ability to maintain energy efficiency, indoor environmental quality (IEQ), and resilience against climate-related stressors. Understanding how well the building envelope performs under various environmental conditions allows for data-driven decisions that guide maintenance and upgrades.

For each building, the current energy performance is measured in a metric called EUI, which stands for Energy Use Intensity and is measured in kBTU/s.f./year.

Nelson Building Current EUI: 257.6 kBTU/s.f./year

Bloch Building Current EUI: 336.6 kBTU/s.f./year

Linda Hall Library Current EUI: 76.0 kBTU/s.f./year

TABLE 4 — Executive Summary Table: How to Evaluate Current Envelope Performance

High-level view for administrators, trustees, board members, planning directors, etc.

(Focus: What’s being evaluated? Why does it matter? What decisions does it influence?)

| Performance Category | What It Measures | Why It Matters for Operations & Risk | Institutional Decision Impact |

| Insulation & Thermal Resistance | R-values, U-values, thermal bridging | Influences energy use, comfort, and HVAC load; impacts long-term operating cost | Guides capital decisions for insulation retrofits, window upgrades, and roof improvements |

| Air & Moisture Infiltration | Leakage through windows, doors, penetrations; moisture intrusion | Affects energy waste, mold/mildew risk, IEQ, and potential damage to finishes | Determines prioritization of weatherization, envelope sealing, and drainage investments |

| Structural Vulnerability to Climate Stress | Response to wind, rain, heat, freeze–thaw cycles, UV exposure | Directly affects resilience, maintenance cost, and safety during extreme weather | Drives mitigation planning, capital repair sequencing, and resiliency investments |

| Impact on Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) | Temperature stability, air quality, humidity, drafts, condensation | IEQ influences staff/patron comfort, artifact protection, and energy performance | Critical for collection care policy, HVAC strategy, and occupant wellness goals |

| Material Condition & Lifespan | Age, degradation, compatibility, deterioration of walls, windows, roofs | Helps avoid unexpected failures and preserves architectural/historic value | Supports long-term capital planning and prioritization of preservation vs. replacement |

| Climate & Carbon Impact | Operational energy load due to envelope deficiencies | Envelope quality drives long-term carbon footprint and cost volatility | Influences sustainability planning, grant funding strategies, and carbon neutrality goals |

TABLE 5 — Technical Diagnostic Matrix: Current Envelope Performance

For engineers, architects, envelope consultants, facility operators, contractors.

| Performance Area | What Is Evaluated | How It Is Measured / Tools | Typical Issues Identified | Implications |

| Insulation Properties & Thermal Resistance | Wall/roof insulation levels; glazing U-values; foundation thermal behavior | Energy modeling, thermography, material sampling, ASHRAE comparisons | Missing insulation, wet insulation, thermal bridging, low-performing glazing | Elevated heating/cooling loads, temperature swings, condensation risk |

| Thermal Bridging Analysis | Conductive pathways across structural elements | IR scans, detail review, 3D heat flow models | Hot spots at sills, steel frames, roof-wall junctions, penetrations | Energy loss, comfort issues, moisture condensation at cold surfaces |

| Air Infiltration | Leakage through fenestration, joints, penetrations | Blower door tests, smoke tests, thermography | Leaky doors, window seals, MEP penetrations not air-sealed | Energy waste, drafts, humidity load increase, pollutant entry |

| Moisture Infiltration & Vapor Movement | Bulk water entry + vapor diffusion through assemblies | Moisture meters, IR scans, wall probes, hygrothermal modeling | Wet cavities, leaks at flashing, condensation in wall cores | Mold, interior finish damage, corrosion, freeze–thaw deterioration |

| Structural Vulnerabilities to Climate Stress | Wind response, water shedding, temperature cycling, freeze–thaw | Visual inspection, drone surveys, crack mapping | Loose masonry, failing mortar, glazing movement, roof membrane fatigue | Risk during storms, safety concerns, accelerated degradation |

| IEQ/Comfort Impacts | Indoor temperature consistency, humidity, air quality | Data logging, BMS trending, thermal comfort surveys | Cold/hot zones, condensation on glass, stagnant air | Increased HVAC demand, occupant discomfort, conservation risks |

| Material Condition Assessment | Roof, walls, windows, foundations | Drone imaging, lift-based inspection, core sampling, façade surveys | Spalling brick, UV-degraded membranes, sealant failure, efflorescence | Predictive maintenance needs, preservation risk |

| Operational Energy Impact | Energy waste due to envelope deficiencies | Energy modeling (pre/post FIM), utility analysis | Disproportionate HVAC consumption, peak load sensitivities | Direct cost impact; informs ROI on envelope upgrades |

| Historic Preservation Constraints | Compatibility of new materials, reversibility | Conservation guidelines, SHPO/NPS standards | Inappropriate materials, risk to historic fabric | Limits approach; guides reversible/low-impact solutions |

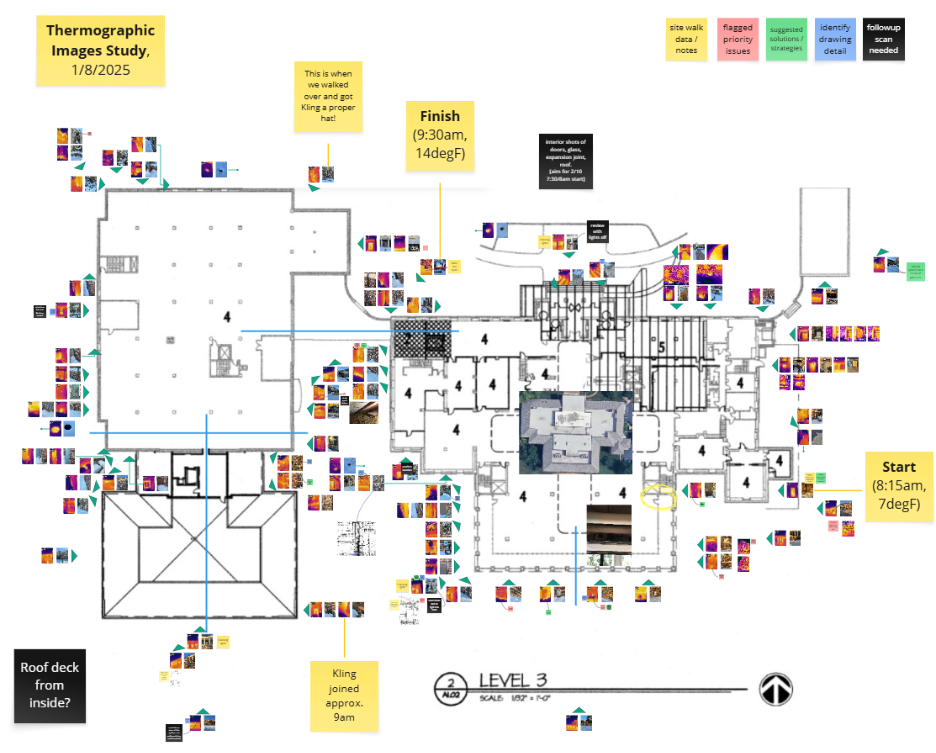

Thermographic Scans of Institutional Buildings in Kansas City, Mo.

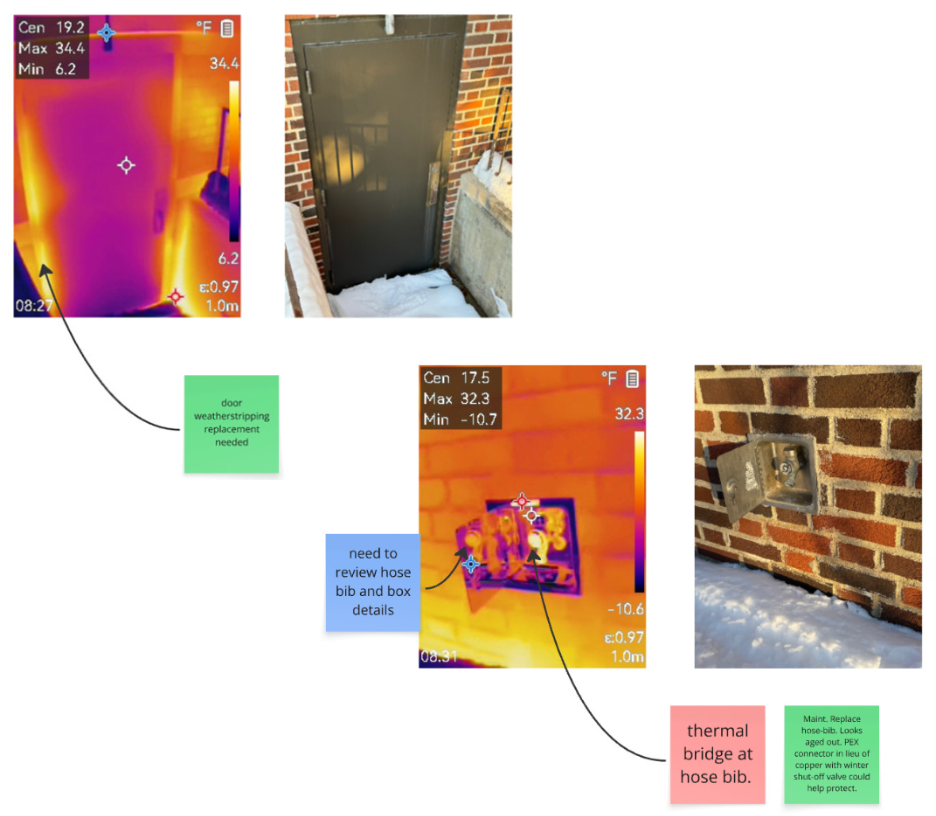

FIGURE 6 — NAMA Campus IR Scans, January 20th, 2025

An example of still images and accompanying thermographic scans taken around the Nelson Atkins Museum of Art on January 20th. Study was conducted when outdoor ambient temperatures were around 5°F/-15°C. The images documented current conditions of the building envelope and identified several areas of concern.

FIGURE 7 — Linda Hall Library Building and Grounds IR Scans, January 8th, 2025

See More In Depth: https://miro.com/app/board/uXjVGJNpD8E=/?share_link_id=419984562006

Still images and accompanying thermographic scans taken around the Linda Hall Library on January 8th. Study was conducted when outdoor ambient temperatures were between 7°F/-14°C and 14°F/-10°C. Like the comparable Nelson studies, the images documented current conditions of the building envelope and identified several areas of concern.

FIGURES 8 & 9 — Common Findings from Infrared Scans

In Figure 8, yellow banding along the door frame indicates heat loss via conduction. The thermal “flaring” indicates heat loss via exfiltration. Fixes include replacing door and frame with thermally broken materials and routinely fixing door sweeps and weatherstripping to stop infiltration/exfiltration.

In Figure 9, conductive heat loss is commonly found where MEP items like hose bibbs and exterior electrical outlets interrupt the building envelope. In this example, highly thermally conductive metal piping pierces the building envelope creating a thermal highway between the indoors and outdoors. As the temperatures dropped in early 2025, it created a large temperature difference between the indoor and outdoor environments, which fuels heat loss (or conversely heat gain in the summer). A simple fix is to replace a portion of the metal piping near the building envelope with PEX or another material with dramatically lower thermal conductivity.

Material Analysis & Lifespan

The material analysis and lifespan assessment are critical components in evaluating the existing building envelope. These assessments help determine the current condition of structural components, identify risks associated with thermal bridging and material degradation, and ensure that any upgrades or replacements comply with historic preservation requirements, wherever necessary. The goal is to enhance energy efficiency, extend the functional life of the envelope, and maintain the aesthetic and architectural integrity of the structures.

Historic Nelson Building – Envelope Analysis and Lifespan

Exterior Walls

The original limestone and multi-wythe brick masonry walls of the historic Nelson building are emblematic of early 20th-century institutional construction and remain in generally excellent structural condition. Field assessments and visual inspection confirm the integrity of the stone cladding and the bedding mortar, with only isolated areas showing minor surface erosion or biological staining — typically along the horizontal surfaces of the sills and base courses. Lower elevations where splash-back occurs was not observed to be an issue because the base course is marble. While the stone itself is highly durable, the wall assembly lacks insulation and vapor control layers (the existing interior surfaces have a layer of cork insulation, less than 1” thick, over an application of what appears to be a coal tar, which we assume was intended as the adhesive, and would provide some vapor diffusion control). However, none of these would provide a level of moisture control appropriate for current standards. Observed issues such as mortar cracking near expansion joints and differential soiling patterns suggest uneven drying or minor water ingress, though no systemic failures were identified. Given its massive thermal mass and robust construction, the lifespan of the wall assembly is exceptional; however, interior environmental control would greatly benefit from discreet insulation strategies, such as vapor-open interior wall assemblies compatible with preservation standards.

Windows

The historic bronze-framed windows — many with original glazing and some with added exterior storms — contribute greatly to the building’s architectural identity but pose known thermal and air infiltration challenges. Thermal imaging indicates significant heat loss and perimeter air leakage, particularly at hinged, operable sashes. Condensation staining is visible on select units, especially on the north and east elevations, though no glazing failure was observed. Many windows are single-pane and lack weatherstripping, making them ill-suited for modern thermal expectations. Nonetheless, most frames appear structurally sound and offer an excellent candidate for secondary interior storm window systems, which could improve thermal performance and air sealing without compromising historical character. If implemented with appropriate venting and low-e coatings, such retrofits could double or triple window R-values and extend the life of the original units.

Roofs

The historic Nelson building is predominantly capped with low-slope SBS bitumen roofing system — finished in a dirty off-white granular surfacing that is starting to wear off, exposing the mod-bit. Additionally, a patinaed, copper standing seam metal roofs sits over the central and flanking sloped sections. The low-slope roofs appear generally uniform but show evidence of age and repeated maintenance, including patching around mechanical curbs, roof penetrations, and perimeter edges. These areas, along with localized staining and past ponding marks, suggest that while the membranes are still serviceable, they may be nearing the point where more comprehensive renewal will be needed to manage long-term water tightness and thermal performance. As noted, the granular surfacing is starting to wear off, exposing the mod-bit to solar/UV degradation, which is the beginning of the end for these systems. Insulation thickness across these roofs is unknown but is likely below current best practice. Ideally, this would make the Nelson building a strong candidate for added above-deck insulation. However, the ‘gravel stop’ edge condition and no parapets precludes any opportunity to add insulation and maintain the internal drainage. Under-deck insulation should be considered carefully with the building’s humidification strategy before implementing. High-SRI “cool roof” coatings at the time of re-roofing to reduce heat gain and cooling loads.

The sloped patina copper standing seam metal roofs are visually distinctive and appear to be in good overall condition, with consistent color and no obvious large-scale distortion or panel failure visible from aerial imagery. These assemblies are expected to have a long remaining service life if regularly maintained at seams, fasteners, and transition flashings. Collectively, the roofing systems offer a solid structural base but present a significant opportunity for thermal upgrades, reflectance improvements, and enhanced drainage detailing that would extend roof life, improve resilience to extreme weather, and reduce overall energy use.

Foundation

The Nelson building’s deep masonry foundation walls were constructed for durability, and they appear structurally sound with no active settling observed. However, these assemblies are uninsulated, and infrared scanning confirms continuous thermal bridging and sub-slab heat loss, particularly along perimeter zones. Groundwater infiltration is minimal, but vapor migration through porous foundation walls likely contributes to elevated RH levels in lower-level storage spaces. As part of any future envelope upgrade, foundation insulation — such as interior rigid or spray-applied vapor-open insulation systems — could dramatically reduce winter heat loss while maintaining wall breathability. Careful detailing would be essential (i.e., a thermal/ignition barrier would be required over spf) to avoid trapping moisture in the stone, but such upgrades offer a promising path to improved comfort and efficiency in subgrade areas.

Bloch Building – Envelope Analysis and Lifespan

Exterior Walls (Channel Glass Wall System)

The Bloch Building is defined by its expressive, translucent façade — constructed primarily from channel glass (U-profiled glass) and conventional curtain wall glazing systems. While visually iconic, this glass-dominant envelope poses ongoing challenges in terms of thermal performance (e.g., heat loss). Solar heat gain and moisture control are not significant issues. The curtain wall framing system is now nearly two decades old. Some thermal-flanking issues occur but are not due to the extrusions. All aluminum extrusions for the channel glass are thermally broken and the steel mullions for the vision glass are all structural silicone glazed with no metal extending through the insulation plane of the IGUs. During infrared testing, elevated surface temperatures were observed on both glass and framing during peak sun conditions, contributing to increased HVAC loads and occupant discomfort in perimeter zones. There is no evidence of major glazing failures, though sealant degradation (minimal) and surface hazing (typically a chemical or mineral residue on the glass) are emerging in high-exposure areas. The surface hazing, however, is easy to clean, which means it does not have a permanent impact on the system (e.g., chemical etching of the glass). Complete replacement of the channel glass wall system may eventually be considered to achieve significant thermal improvements but would be difficult to enhance compared against the existing steel framed SSG system; about the only thing that could be done that would have a positive effect would be new IGUs with higher performance Low-E coatings, Argon fill, and warm edge spacers.

Windows & Transparent Assemblies

Curtain wall and other non-channel glazing systems are found throughout. Glazing performance throughout the Bloch Building remains its most significant energy liability. The best opportunity to enhance performance is with newer glass, with argon filling, warm-edge spacers, or perhaps vacuum glass and better coatings to improve the performance of extensive solar heat gain and glare — especially on southern and western exposures. Internal shading devices are inconsistently used. Hardware and operability issues were not prevalent, but condensation risks remain, particularly where interior humidity is elevated and interior surface temperatures drop below the dew point.

Roofs

The Bloch Building’s flat, single-ply membrane roof is typical of contemporary lightweight construction. Though generally in stable condition, the roof exhibits inconsistent insulation coverage and lacks reflective or green roof strategies that could help mitigate Urban Heat Island impacts. Drainage patterns appear functional, though ponding was observed during earlier site visits at expansion joints and roof perimeter edges. The absence of a vegetative or cool roof strategy means roof surface temperatures remain high during summer months, contributing to internal heat gain. As the roofing system approaches mid-life, retrofits involving added insulation and high-SRI membrane replacement should be explored. If the structure allows, expanding modular green roof systems may also be viable for portions of the building, adding stormwater and microclimate benefits. A recent undertaking by the Museum will enhance both the insulation and reflectance of the roof, thereby lowering the energy intensity and reliance on HVAC.

Foundation

The Bloch Building is extensively and deeply embedded into the site, with more than half of its volume located below grade. This configuration provides significant thermal buffering compared to a fully above-grade structure, but it also introduces elevated risks related to groundwater, lateral moisture migration, and humidity control in subgrade gallery and circulation spaces. The foundation system consists of cast-in-place concrete foundation walls and slabs bearing against retained earth, with select areas transitioning to slab-on-grade conditions nearer the exposed ends of the building. Visual observation and available performance data suggest that, while there are no widespread signs of structural distress, isolated instances of minor seepage, localized dampness, or condensation at floor–wall and glass–floor interfaces have occurred over time — particularly where glazing extends close to grade or where exterior drainage paths are complex. The below-grade construction offers a strong, durable structural base insulated and damp-proofed to provide additional resilience for thermal and moisture performance.

Climate Risk & Environmental Footprint Considerations

The building envelope of the Nelson Atkins Museum of Art is critical in mitigating climate risks and minimizing environmental impacts. Climate change has increased the frequency and intensity of weather events, exposing historic structures to unprecedented environmental stressors. This section addresses climate adaptation factors, carbon and energy impact analysis, and the long-term sustainability of the current building envelope materials.

TABLE 6 — Essential Climate Adaptation Matrix

(Summary table for administrative personnel)

| Climate Factor | Primary Risks | Building Type Sensitivity | Most Effective Mitigations | Who Needs to Act |

| Temperature Extremes | Thermal expansion, material fatigue, glazing stress, heat gain, delayed cooling | Lightweight (Bloch): highest heat sensitivity; Mediumweight (LHL): thermal mass delays cooling; Heavyweight (Nelson): long thermal lag and nighttime heat release | Dynamic glazing, shading devices, thermal breaks, internal insulation (vapor-open), reflective coatings, controlled night purge | Envelope consultants, HVAC team, preservation staff |

| Precipitation Changes | Water intrusion, glazing joint failures, freeze–thaw cycles, foundation movement, efflorescence | Lightweight: infiltration at joints; Medium: masonry saturation, salt migration; Heavy: deep moisture retention, prolonged drying | Sealant upgrades, rainscreens, drainage mats, repointing with appropriate mortar, French drains, breathable water repellents | Facilities, preservation, landscape |

| Storm Resilience | Wind uplift, impact risk to glazing, parapet failure, structural vibration, roof drainage overload | Lightweight: highest wind/impact risk; Medium: failures at parapets, openings; Heavy: risk at cornices, loose stone | Impact-resistant glazing, reinforced parapets, upgraded flashing, drainage improvements, added anchors/bracing | Structural engineers, envelope specialists, contractors |

| Humidity Management | Condensation, mold, corrosion, plaster damage, microclimate instability for collections | Lightweight: condensation at glazing; Medium: cavity moisture, corrosion of steel; Heavy: trapped moisture in thick walls | Thermally broken frames, improved glazing, in-wall sensors, zoned dehumidification, vapor-open interior insulation | HVAC, conservation staff, envelope consultants |

| Urban Heat Island (UHI) | Increased cooling loads, faster material aging, occupant discomfort, stress on collections | Lightweight most affected; Medium/Heavy moderately affected | Cool roofs, green roofs, high-albedo paving, perimeter tree canopy, dynamic shading, HVAC zoning | Planning, landscape, sustainability teams |

TABLE 7 — Consolidated Technical Climate Adaptation Table

(For technical readers: engineers, architects, facilities operators)

| Impact Category | Lightweight (Bloch Building) | Mediumweight (LHL) | Heavyweight (Nelson Building) | Cross-Building Mitigation Toolkit |

| Temperature Extremes | High solar gain; glazing sealant failure; material warping | Heat storage delays cooling; thermal bridging; masonry cracking | Long thermal lag; nighttime heat release; stone expansion | Dynamic glazing, shading devices, thermal breaks, enhanced insulation, flexible sealants, controlled night purge |

| Changes in Precipitation | Wind-driven rain infiltration; glazing staining; foundation heave | Brick saturation; freeze-thaw spalling; salt migration | Deep moisture penetration; prolonged drying; plaster damage | Drainage improvements, breathable coatings, mortar repointing, capillary breaks, improved grading, rainscreens |

| Storm Resilience | High wind pressure on glass; risk of impact failure; façade deflection | Wind-driven damage at parapets/openings; moisture infiltration at joints | Loose masonry components; parapet/cornice failure potential | Impact-resistant glazing, reinforced parapets, structural anchors, improved flashing, aerodynamic landscape elements |

| Humidity Management | Interior condensation on glass; mold risk; metal frame corrosion | Cavity moisture, corrosion of framing, interior finish degradation | Moisture retention in masonry; efflorescence; plaster failure | Thermally broken frames, HVAC dehumidification, vapor-open insulation, moisture sensors, internal humidity zoning |

| Urban Heat Island | Overheating; HVAC oversizing; glazing hot spots | Moderate overheating; reduced passive performance | Material temperature cycling; increased roof temp | Cool roofs, green roofs, shading, reflective paving, landscape buffers, sensor-driven HVAC zoning |

Climate Adaptation Factors

Climate adaptation is essential to protect the building envelope from anticipated climate shifts and environmental stressors. Both institutions face unique challenges, including temperature extremes, storm resilience, humidity management, and the urban heat island effect.

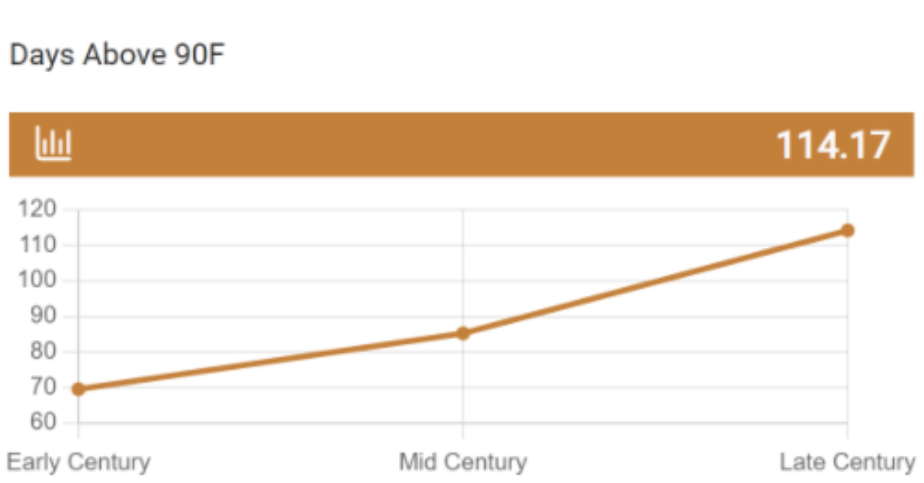

FIGURE 8 — Temperature Extremes Shifting over time in Kansas City, Mo. Days over 90°F

FIGURE 9 — Temperature Extremes Shifting over time in Kansas City, Mo. Days over 100°F/110°F

TABLE 8 — Climate-responsive Envelope Adjustments

| Climate Factor & Building Type | Key Vulnerability | Primary Envelope Adjustments (Climate-Responsive) | Supporting Ops / Systems Notes | Suggested Priority |

| Temperature Extremes – Bloch (Lightweight) | High solar gain through clear glazing; rapid interior overheating; sealant and frame stress from thermal cycling. | •Replace clear glass with low-e or electrochromic glazing in existing frames where feasible. • Add external shading (fins, louvers, landscape screens) at west/south façades. • Introduce thermally broken framing and improved gaskets in phased curtain wall replacements. | Coordinate with HVAC for zoned cooling and night purge strategies to relieve stored heat in glass/structure. | Near-Term (glass and shading upgrades); Mid-Term (frame/curtain wall replacement). |

| Temperature Extremes – Nelson (Heavyweight) | Long thermal lag; walls and roofs store heat through multi-day heat waves, radiating inward at night. | • Apply cool/reflective roofing on low-slope roofs. • Use vapor-open interior insulation (e.g., aerogel plaster) on high-gain interior walls. • Add select shading at high-exposure façades without altering historic character. | Implement night purge ventilation and climate-aware setpoints that reflect wall mass behavior. | Mid-Term, phased with roof renewals and interior restoration. |

| Precipitation Changes – Bloch (Lightweight) | Wind-driven rain at curtain wall joints; staining and sealant degradation; localized leaks at interface details. | • Systematic re-sealing of curtain wall joints, gaskets, and transitions. • Integrate drainage channels/pressure-equalized joints in any curtain wall replacement. • Add permeable landscape and rain gardens at base to manage splash-back and runoff. | Link to inspection/maintenance plan for sealants; BMS alarms for leak detection and humidity spikes in perimeter zones. | Near-Term (sealants & drainage); Ongoing (maintenance regime). |

| Precipitation Changes – Nelson (Heavyweight) | Deep moisture penetration into thick stone/brick; very slow drying; risk of plaster damage and efflorescence. | • Install capillary breaks or interior drainage planes where feasible. • Use silane/siloxane breathable water repellents on select exposures. • Upgrade roof and parapet flashing, drip edges, and base detailing to keep water off wall faces. | Pair with targeted dehumidification in perimeter galleries and lower levels to support inward drying when appropriate. | Mid-Term, phased by façade and coordinated with preservation work. |

| Storm Resilience – Bloch (Lightweight) | High wind and impact risk at large glazed surfaces; façade acts like a “sail.” | • Introduce laminated/impact-resistant glass in critical zones. • Strengthen curtain wall anchorage and bracing at corners and high-exposure faces. • Improve roof-to-wall fastening and edge metal. | Coordinate with emergency operations for severe-weather shuttering protocols and safe refuge areas. | Near-Term at critical zones; Mid-Term campus-wide. |

| Storm Resilience – Nelson (Heavyweight) | Rigid masonry with localized weakness at cornices, projections, and decorative elements. | • Concealed anchors/ties at cornices, balustrades, and stone projections. • Stabilize or rebuild deteriorated parapets and chimneys. • Improve foundation waterproofing where stormwater accumulates. | Use drone/photogrammetry to monitor displacement and cracking after major events. | Near-Term at highest-risk elements; Ongoing monitoring. |

| Humidity Management – Bloch (Lightweight) | Condensation on glazing/frames; corrosion; high sensitivity of interiors and collections to RH swings. | • Upgrade to thermally broken frames and high-performance IGUs. • Improve air sealing at frame interfaces and penetrations. • Coordinate with zoned dehumidification in galleries. | Move HVAC-specific items to Building Systems; maintain 40–55% RH with continuous monitoring. | Near-Term (sealing, controls); Mid-Term (frame/glazing replacement). |

| Humidity Management – Nelson (Heavyweight) | Long-term moisture storage in thick walls; efflorescence; plaster and finish degradation. | • Use vapor-open interior insulation (e.g., aerogel plasters). • Apply breathable water-repellent treatments on select façades. • Improve ventilation in perimeter rooms to reduce surface humidity. | Pair with dedicated dehumidification and smart controls responding to envelope moisture behavior. | Mid-Term, coordinated with interior conservation work. |

| Urban Heat Island – Bloch (Lightweight) | Overheating at roof and glazed façades; high cooling loads; hot exterior plazas. | • Install cool roof or modular green roof systems. • Add external shading and high-albedo paving around the building. • Integrate landscape buffers and tree canopy for microclimate relief. | Use sensor-driven HVAC zoning and lighting/shading coordination during heat events. | Near-Term (shading/paving changes); Mid-Term (roof conversions). |

| Urban Heat Island – Nelson (Medium/ Heavyweight) | Elevated roof temps and material cycling; modest overheating in perimeter spaces. | • Retrofit high-SRI membranes on low-slope roofs. • Increase tree canopy and permeable surfaces around the buildings. • Use light-colored façade or trim coatings where preservation allows. | Tie into broader campus UHI strategy and long-term carbon planning. | Mid-Term, aligned with roof replacements and landscape projects. |

TABLE 9 — Aerogel Plaster Properties (Imperial Units)

| Property | Value/Benefit |

| Thermal Conductivity | As low as 0.125-0.173 BTU·in/hr·ft² · °F – extremely efficient compared to traditional lime or gypsum plasters |

| Thickness | Effective insulation at ¾ “2 in – ideal where interior space is limited |

| Vapor Permeability | μ-value between 5-10, meaning it’s highly breathable |

| Hydrophobic yet Breathable | Repels bulk water but allows vapor diffusion – avoids trapped moisture. |

| Fire Resistance | Typically non-combustible (Class A or Euroclass A1) |

| Reversible & Compatible | Mineral base makes it chemically and physically compatible with historic masonry and lime mortars |

TABLE 10 — Aerogel Plaster Performance Benefit Snapshot (Imperial Units)

| Feature | Aerogel Plaster | Traditional Lime Plaster |

| Thermal Conductivity | 0.125–0.173 BTU·in/hr·ft²·°F | ~0.52–0.69 BTU·in/hr·ft²·°F |

| Thermal Insulation | ★★★★★ (very high) | ★ (very low) |

| Vapor Permeability | ★★★★ | ★★★★★ |

| Historic Compatibility | ★★★★ | ★★★★★ |

| Application Thickness | Thin (¾–2″) | Moderate (⅝–1¼”) |

Carbon & Energy Impacts

Operational energy consumption and carbon impacts from envelope deficiencies are meaningful. Below is a description of these impacts.

Nelson Building

As part of the ongoing effort to evaluate energy performance at the historic Nelson building, a targeted set of envelope-focused energy conservation strategies has been studied to address thermal inefficiencies while respecting the building’s historic character. These strategies aim to improve energy efficiency, occupant comfort, and long-term resilience, all while preserving the integrity of the original structure. Key measures include roof insulation and reflectance improvements, selective upgrades to existing glazing systems using low-emissivity coatings or discreet secondary glazing, and enhanced airtightness through refined air sealing at doors, windows, and envelope penetrations. Additionally, the strategies include thermal improvements to uninsulated foundations and above-grade opaque walls through minimally invasive, interior insulation solutions. These conservation measures form the basis for estimating future energy savings and environmental performance, pending the final results of the energy modeling analysis.

TABLE 12— Proposed Energy Strategies for the Nelson Building

| Category | Improve Roof Performance | Improve Curtain Wall | Improve Non-Curtain Wall Glass Performance | Improve Building Tightness | Insulate Foundations | Improve Opaque Wall Performance |

| Primary Strategy | Add insulation to roof deck | Replace curtain wall glass with optimized low-e glass | Apply low-e coating to surface #1 of existing glass | Reduce infiltration / exfiltration via envelope air sealing | Add continuous foundation insulation | Add interior insulation to exterior walls |

| Secondary Strategy | Improve roof reflectance (SRI) | Replace curtain wall glass with electrochromic glass | — | Door sweeps, horsehair, gaskets; seal MEP penetrations | — | Interior furring and insulation |

| Baseline Condition (from GDS) | Existing roof insulation (limited by roof condition) | Existing curtain wall glazing | Existing non-curtain wall glazing | Existing envelope leakage rates | R-0 (uninsulated) | Existing opaque wall assemblies |

| Proposed Target / New Value | SRI ≈ 70 (reflectance improvement) | High-performance glazing (low-e or electrochromic) | Low-e surface-applied coating | Significantly reduced infiltration (verified via testing) | R-10 continuous | Improved effective wall R-value |

| Key Technical Notes | Existing roof condition limits insulation thickness; additional insulation may be unrealistic | Electrochromic glass evaluated for solar control benefits | Data pending; coating performance under review | Highest modeled energy savings across all envelope measures | No occupied space below grade; feasibility constrained | Reviewing prior improvements and remaining opportunities |

| Uncertainty / Open Items | Structural limits and reroof timing | Cost vs. benefit of electrochromic option | Performance data still being evaluated | Requires commissioning and verification | Below-grade access constraints | Preservation-sensitive detailing |

| Relative Priority | Medium | Medium–High | Medium | High (Tier 1) | Medium | Medium |

| Primary Benefits | Reduced heat gain; roof longevity | Reduced solar gain; glare control; comfort | Lower radiant heat transfer | Energy savings; comfort; moisture risk reduction | Improved perimeter comfort | Reduced thermal bridging; improved comfort |

Bloch Building

As part of the ongoing analysis of the Bloch Building’s energy performance, a set of envelope-related energy conservation strategies has been studied to address its unique challenges as a lightweight, glass-heavy structure. These strategies focus on reducing solar heat gain, improving thermal performance, and enhancing the building’s responsiveness to climate-related stresses. Key measures include roof upgrades with added insulation and high-reflectance materials, improvements to the curtain wall system through optimized low-emissivity glazing or dynamic electrochromic glass, and retrofits to other glazing areas with surface-applied low-e coatings. Infiltration control measures have also been identified, including enhanced air sealing at doors, glazing interfaces, and mechanical penetrations. Together, these strategies aim to improve year-round energy efficiency and occupant comfort while supporting the building’s curatorial and operational needs. Final energy savings estimates are forthcoming pending the results of ongoing energy modeling.

TABLE 13— Proposed Energy Strategies for the Bloch Building

| Category | Improve Roof Performance | Improve Curtain Wall | Improve Non-Curtain Wall Glass Performance | Improve Building Tightness | Insulate Foundations | Improve Opaque Wall Performance |

| Primary Strategy | Add insulation to roof deck | Replace curtain wall glass with optimized low-e glass | Apply low-e surface #1 coating to existing glass | Enhance control of infiltration and exfiltration | Add continuous insulation | Add insulation to exterior walls from the interior |

| Alternate / Companion Strategy | Improve roof reflectance (SRI) | Replace curtain wall glass with electrochromic glass | — | Door sweeps, horsehair, gaskets; seal MEP penetrations | — | Interior furring with insulation |

| Baseline Condition | Existing roof assembly (from GDS) | Existing curtain wall glazing (from GDS) | Existing non-curtain wall glazing (from GDS) | Existing envelope leakage rates | Uninsulated foundations | Uninsulated opaque exterior walls |

| Target / New Value | R-55 roof assembly | High-performance low-e IGUs | Low-e coating applied to existing glass | Reduced infiltration via comprehensive air sealing | R-15 continuous | Improved effective wall R-value |

| Key Notes | Stretch target — improves resilience and long-term performance | Electrochromic option provides dynamic solar control | Limited disruption; cost-effective thermal upgrade | Highest modeled energy savings across all buildings | Limited below-grade access may constrain feasibility | Preservation-sensitive detailing required |

| Implementation Considerations | Structural capacity; reroof timing | Curtain wall system compatibility | Glass condition and coating suitability | Commissioning and verification critical | Moisture control and drying potential | Vapor-open assemblies preferred |

| Relative Priority | Medium | Medium–High | Medium | High (Tier 1) | Medium | Medium |

| Primary Benefits | Reduced heat loss/gain; roof durability | Reduced solar gain; comfort; glare control | Lower radiant heat transfer | Energy savings; comfort; moisture control | Improved perimeter comfort | Reduced thermal bridging; comfort |

Facility Improvement Measures (FIMs) for Envelope Optimization

Thermal & Moisture Control Improvements

Improving the thermal and moisture performance of building envelopes is one of the most impactful and cost-effective strategies for reducing energy use, enhancing occupant comfort, and improving long-term durability. Across the studied facilities — including the historic Nelson building, Linda Hall Library, and the Bloch Building — specific Facility Improvement Measures (FIMs) have been identified to reduce heat transfer, mitigate moisture risks, and preserve envelope integrity while supporting operational and preservation goals.

High-Performance Insulation Upgrades

Enhanced insulation is fundamental to improving thermal resistance and stabilizing indoor temperatures year-round. Across the sites, strategies have focused on:

- Added Roof Insulation: Many roof systems currently lack optimal thermal resistance. Upgrades will include added insulation above the deck or in attic spaces to reduce heat loss in winter and heat gain in summer, particularly important for large roof surfaces such as those at Linda Hall Library and the Bloch Building.

- Aerogel, Vacuum-insulated Panels, or Bio-based Insulation Materials: These advanced insulation materials offer high R-values in thinner assemblies, making them ideal for space-constrained areas and historic applications where minimal visual or structural impact is required.

- Internal Insulation Strategies for Historic Preservation Compatibility: For historic buildings like the Nelson, internal furring systems and vapor-open insulation options will be used to avoid exterior alterations while still improving envelope performance.

- Below-Grade Insulation: Foundation walls — often uninsulated — are key contributors to heat loss and moisture ingress. Continuous insulation strategies at foundation walls and slab edges are proposed to improve energy performance and reduce condensation risk.

Advanced Weatherization Strategies

Controlling air and moisture movement through the building envelope is critical to reducing energy waste and protecting interior materials.

- Air Barrier and Vapor Control Enhancements: The integration or reinforcement of air barrier systems and smart vapor retarders can dramatically reduce uncontrolled infiltration and condensation risks. These measures will be tailored to wall assemblies to maintain drying potential, particularly in mass masonry structures.

- Window and Door Sealing Improvements: Targeted weatherization at operable joints — through the use of new gaskets, sweeps, horsehair insulation, and precision sealants—will reduce infiltration at known leakage points. This strategy is particularly valuable for older fenestration systems and frequently used public entries.

Energy-Efficient Fenestration & Daylighting

Windows and glazed elements play a critical role in the thermal performance, visual comfort, and energy use of each facility. Targeted upgrades to fenestration systems are key to reducing solar heat gain, improving insulation, and protecting sensitive interior environments such as galleries and archives. These strategies also enhance daylighting quality — balancing natural illumination with solar control to reduce reliance on electric lighting and improve occupant well-being.

High-Performance Windows & Glazing Retrofits

Upgrades to existing glazing systems were studied across all facilities, with each building requiring a tailored approach based on envelope construction, operational needs, and preservation priorities:

- Low-E Coatings: Applying or upgrading to low-emissivity (low-e) coatings on existing or new glazing significantly improves thermal performance by reducing radiant heat transfer while maintaining visible light transmission. This strategy is applicable across all buildings and forms the baseline for many retrofit scenarios.

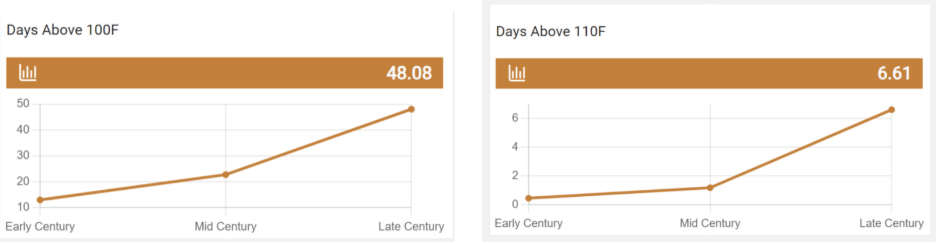

- Dynamic Glazing (Electrochromic and/or Thermochromic): Dynamic glazing (See Figures 12 & 13) technologies automatically tint based on light and temperature conditions, reducing solar gain and glare without sacrificing views or daylight. This is particularly beneficial in highly glazed buildings like the Bloch Building, where large surface areas are exposed to direct sunlight.

- Secondary Interior Storm Windows for the Nelson Building: For the historic Nelson building, interior secondary glazing systems are proposed to improve thermal performance without altering the exterior appearance. These systems add insulating value and air tightness while preserving the integrity of the original windows.

- UV Protection for Artwork and Archives: Across all buildings, particularly in gallery and archive areas, glazing systems will include integrated UV filtering to protect sensitive materials from photodegradation. This is critical for preserving collections while maintaining access to natural light.

Special note: In figures 10 & 11, the dynamic glazing blocks unwanted parts of the light spectrum, like near-infrared (primary target). In doing so, it often also will dramatically reduce visible light transmittance (VLT). There’s no way around it. Further, it may not be suitable for historic buildings.

FIGURE 10 — Dynamic Glazing in a Low Solar Radiation Environment

FIGURE 11 — Dynamic Glazing in a High Solar Radiation Environment

Daylighting Strategies

Well-executed daylighting reduces energy use and enhances the visual and psychological comfort of occupants. Daylighting strategies are being considered in conjunction with window upgrades to ensure a balanced indoor environment:

- Optimizing Natural Light While Reducing Solar Heat Gain and Glare: Placement, size, and glazing type will be considered holistically to allow for deep daylight penetration while minimizing hotspots and glare. This strategy supports occupant comfort and artifact protection in library and gallery spaces.

- Automated Shading and Light-Reflecting Technologies: To further control light and heat gain, advanced interior and exterior shading systems — such as automated blinds, solar tracking louvers, and light shelves — are recommended. These systems dynamically respond to changing daylight conditions, supporting energy efficiency and preservation goals.

Roof & Exterior Wall Enhancements

Enhancements to roofing systems and exterior wall assemblies present high-impact opportunities to reduce heat gain, improve insulation, and manage stormwater—particularly in the face of rising temperatures and increased precipitation variability. These upgrades support both operational efficiency and climate resilience while aligning with institutional sustainability goals across all three facilities.

Cool Roof & Green Roof Installations

Roof surfaces are among the most exposed and underutilized components of the envelope. Upgrades under consideration include:

- Reflective Coatings or Vegetated Roof Systems for Heat Mitigation: Cool roofs—using high-albedo coatings or materials—can significantly lower roof surface temperatures, reducing building cooling loads and mitigating the Urban Heat Island effect. Where feasible, green roofs (vegetated systems) offer added thermal performance and support stormwater absorption, biodiversity, and microclimate regulation. These strategies are particularly applicable to low-slope or flat roof areas at Linda Hall Library and the Bloch Building.

- Improved Stormwater Management and Insulation Benefits: Green roofs not only insulate against temperature extremes but also absorb and slow rainwater runoff, reducing pressure on stormwater infrastructure. In retrofits, adding rigid insulation beneath roof membranes can improve thermal resistance while integrating drainage layers and root barriers for green roof compatibility.

Sustainable Façade Materials

Exterior walls offer opportunities for material replacement or reinforcement with low-carbon, high-performance alternatives — particularly during major envelope renovations or localized repairs.

- Replacing or Reinforcing Facade Elements with Carbon-Neutral Materials: When restoring or upgrading wall cladding systems, the use of carbon-neutral or low-embodied-carbon materials — such as reclaimed brick, lime-based stucco, or natural fiber panels — can reduce lifecycle emissions. These options are evaluated for use on both existing and infill construction areas, with special consideration for material compatibility with historic structures like the Nelson Building.

- Integrating Passive Ventilation Features: Where possible, envelope upgrades will explore integrated passive ventilation strategies, such as operable louvers, ventilated rainscreens, or shading fins that support natural airflow. These strategies not only enhance indoor environmental quality but reduce reliance on mechanical cooling — particularly valuable in temperate seasons and transitional spaces.

Resilience Enhancements

As climate conditions grow more extreme, the building envelope must evolve to not only reduce energy use but also protect occupants, collections, and infrastructure from the increasing risks posed by wind, rain, humidity, and temperature fluctuations. The following resilience enhancements focus on strengthening the envelope’s capacity to withstand environmental stress while supporting long-term durability and adaptive performance.

Storm-Resistant Envelope Design

With more frequent and intense weather events — including windstorms, driving rain, and localized flooding — each facility’s envelope must be prepared to resist water intrusion and structural failure.

- Impact-Resistant Glazing and Reinforced Wall Structures: Replacing vulnerable glazing with laminated, impact-resistant glass is a critical resilience strategy, especially for large, glazed areas like those at the Bloch Building. Reinforcing wall assemblies at vulnerable corners, parapets, and roof-wall transitions can also reduce the risk of structural compromise during high-wind events.

- Sealing Strategies Against Wind-Driven Rain and Flood Risks: Strategic sealing—at windows, doors, and penetrations—reduces vulnerability to water intrusion under pressure. At grade level, perimeter detailing may include flood barriers or raised thresholds to protect against rising water and splash-back during storms.

Climate-Responsive Ventilation & Breathable Walls

Heavy precipitation, humidity spikes, and warmer seasonal temperatures require walls and ventilation systems that manage moisture and airflow effectively.

- Adaptive Materials that Regulate Moisture and Heat Dynamically: New material technologies—such as hygrothermal insulation, phase-change materials, and vapor-open aerogel plasters—offer the ability to buffer interior conditions without sealing in moisture, especially in heavyweight masonry buildings like the Nelson.

- Hybrid Ventilation Strategies Integrated with Envelope Design: Ventilation systems that combine passive and mechanical methods, such as operable louvers, stack ventilation paths, or ventilated cavities behind rainscreens, offer seasonal flexibility while reducing strain on mechanical systems.

Moisture Control

Moisture control is fundamental to both resilience and material preservation, especially in aging or historic buildings.

- Stormwater Conveyance: Roof and site drainage improvements — including scuppers, gutters, downspouts, and perimeter drains — ensure that water is quickly diverted away from envelope components and foundations, reducing the risk of water ingress and foundation deterioration.

- Flashing, Rainscreens, & Drip Edges: Proper detailing of flashing and overlapping layers at transitions (e.g., window heads, parapets, roof-wall junctions) prevents water tracking and encourages drainage. Rainscreen systems allow wall assemblies to dry and buffer against external moisture.

- Vapor Barriers & Retarders: Strategic placement of vapor control layers — particularly in walls that must insulate from both heat and moisture — prevents condensation within assemblies while allowing drying potential based on building type and regional climate.

TABLE 14 — Recommended Facility Improvement Measures (FIMs) for Envelope Optimization

| FIM Category | Specific Measures | Primary Benefits | Applicable Buildings | Implementation Priority |

| 1. High-Performance Insulation Upgrades | • Add above-deck roof insulation • Use aerogel, VIP, or bio-based insulation in constrained areas • Install vapor-open interior insulation for historic walls • Add below-grade & foundation insulation | • Reduced heating/cooling loads • Better perimeter comfort • Lower condensation risk | Nelson (historic) LHL Bloch | Near- & Mid-Term (as roofs/walls are renovated) |

| 2. Air & Moisture Weatherization | • Air barrier continuity upgrades • Smart vapor retarders • Door sweeps, gaskets, horsehair seals • Seal MEP penetrations | • Lower infiltration • Improved humidity stability • Reduced mold & corrosion risks | All buildings | Near-Term (low cost; fast ROI) |

| 3. High-Performance Fenestration | • Low-e glazing upgrades • Dynamic glazing (electrochromic/thermochromic) • Secondary interior storms for historic windows • Full curtainwall replacement at LHL | • Reduced solar gain/glare • Improved thermal performance • Better conservation conditions | Nelson (storms) LHL (curtainwall) Bloch (dynamic glazing) | Near-Term (low-e) Mid-Term (system replacements) |

| 4. Daylighting Enhancements | • Shading devices (automated or fixed) • Reflective interior surfaces/light shelves • Optimize glazing ratios | • Reduced electric lighting use • Reduced glare/solar heat gain • Enhanced occupant visual comfort | Bloch LHL Nelson (select zones) | Mid-Term |

| 5. Roof Performance Improvements | • Cool roof membranes (high SRI) • Modular or extensive green roofs • Added insulation beneath roofing • Roof drainage upgrades (scuppers, tapered insulation) | • Lower UHI impacts • Lower cooling demand • Improved stormwater management | Bloch LHL Nelson (low-slope roofs) | Mid-Term (timed with reroof cycles) |

| 6. Sustainable Façade Upgrades | • Low-carbon cladding materials • Reinforced masonry repairs • Ventilated rainscreens where appropriate • Passive ventilation integration | • Lower embodied carbon • Better moisture drying potential • Improved long-term durability | Nelson (preservation-driven) LHL | Long-Term / Opportunistic (linked to major façade work) |

| 7. Storm & Wind Resilience Enhancements | • Impact-resistant glazing (Bloch) • Reinforced parapets, cornices (Nelson, LHL) • Improved flashing & edge securement • Structural anchors at vulnerable features | • Reduced storm damage risk • Longer façade lifespan • Lower operational disruption | Bloch (highest priority) LHL Nelson | Near-Term for critical zones Ongoing maintenance |

| 8. Climate-Responsive Ventilation & Breathable Wall Assemblies | • Vapor-open insulation (e.g., aerogel interior plaster on Nelson) • Ventilated cavity details • Hybrid (passive + mechanical) ventilation paths | • Improved drying vs. wetting balance • Healthier interior RH profiles • Reduced risk of mold/corrosion | Nelson (critical) LHL | Mid-Term |

| 9. Moisture Control Systems | • Rainscreens and drip edges • Foundation drainage improvements • Flashing upgrades at windows, parapets, and transitions | • Reduced water intrusion • Lower freeze–thaw damage risk • Improved envelope durability | All buildings | Near-Term (drainage, flashing) Mid-Term (rainscreens) |

| 10. Functional Perimeter Enhancements | • Regrading away from foundations • Permeable paving for stormwater reduction • Vegetated buffers/shade trees | • Lower stormwater loads • UHI mitigation • Reduced basement humidity | Nelson LHL Bloch | Mid-Term |

Performance Modeling & Impact Analysis

Project analysts performed extensive modeling exercises for all three buildings. They conducted the models using ASHRAE methodology and tuned the as-built (existing conditions) to the current energy bills within ASHRAE’s specified limits. From there, we tested incremental improvements in building tightness, increased insulation for roofs and foundations, better glazing systems, and high albedo roofs.

Across Linda Hall Library and both Nelson-Atkins buildings (Main + Bloch), the modeling shows a clear pattern: reducing uncontrolled air leakage (improving building tightness) is the most impactful envelope strategy for lowering annual energy cost. In the Nelson-Atkins Main Building and Bloch Building summaries, infiltration reductions similarly produced the largest annual savings, reaching six figures at the more aggressive airtightness scenario.

Other envelope measures showed incremental energy impacts in these specific model runs. Increasing roof insulation produced relatively small annual savings across all buildings (generally a few thousand dollars per year or less). Slab/foundation insulation also modeled as modest from an energy-cost perspective, but it can still be important for perimeter comfort and moisture/condensation control, especially in collection-sensitive environments.

Window and glazing improvements landed in the middle: sometimes modest from a pure utility standpoint, but often pursued for thermal comfort, condensation risk reduction, and daylight/collection management. For example, Linda Hall’s comparison set includes low-e and electrochromic options with measurable (but not dominant) annual savings, while the Nelson-Atkins Main Building summary shows a glazing improvement case at roughly $9,500 per year. Finally, “cool roof” (higher SRI) modeled as essentially neutral in annual savings in this batch of runs, though it may still offer resilience and durability value depending on roof type and exposure.

TABLE 15 — Modeled Energy Savings for Various FIMs Across All Buildings

| Envelope FIM (modeled) | Improvement details | LHL – Utility cost savings | NAMA Main – Utility cost savings | NAMA Bloch – Utility cost savings | Takeaway |

| Improved building tightness / infiltration reduction | Reduced infiltration / improved airtightness | $48,047/yr (largest) | $43,283/yr (0.35 cfm/sf) to $111,029/yr (0.10 cfm/sf) | $52,341/yr (0.35 cfm/sf) to $135,385/yr (0.10 cfm/sf) | Airtightness is the dominant energy lever across all three buildings. |

| Roof insulation increase | Roof R-value increased in steps | $530–$1,099/yr | $1,205–$2,931/yr | $1,197–$3,672/yr | Helpful, but small annual savings compared to airtightness. |

| Slab / foundation-edge insulation | Added slab insulation levels | $1,810–$2,233/yr | $103–$186/yr | ~$628–$632/yr | Energy impact is modest, but can be valuable for comfort + condensation control at perimeter zones. |

| Window / glazing improvements | Improved glazing performance | $1,606/yr (windows); $3,913/yr (electrochromic); $1,006/yr (low-e) | $9,530/yr | (Not shown as a primary lever in summary; airtightness dominates) | Typically comfort/collection protection value is high; modeled energy savings vary by building and glazing area. |

| Cool roof / higher SRI | Increased roof reflectance | $96/yr | ~$0/yr (modeled ~neutral) | $10/yr | Minimal modeled annual savings in these runs (still may help with surface temp + roof longevity). |

| Envelope FIM | Energy impact (modeled) | Comfort & stability | Moisture risk reduction | Durability / O&M | Disruption / complexity | Notes from the modeled results |

| Airtightness / infiltration reduction | High (LHL $48k/yr; NAMA Main up to $111k/yr; Bloch up to $135k/yr) | High | High | Medium | Medium–High | Clear “needle mover” in all three summaries. |

| Roof insulation increases | Low | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium | Consistently small annual savings vs. baseline across all three. |

| Slab / foundation-edge insulation | Low | Medium | Medium–High | Medium | Medium–High | Savings were modest, but perimeter comfort and condensation control can justify it. |

| Glazing upgrades (windows / low-e / electrochromic) | Low–Medium (building dependent) | High | Medium | Medium | High | LHL shows modest savings for low-e + electrochromic vs baseline; NAMA Main shows ~$9.5k/yr for glazing improvement. |

| Cool roof / high SRI | Low (near zero in these runs) | Low–Medium | Low | Medium | Low–Medium | Modeled savings were minimal/neutral in all three summaries. |

TABLE 16 — Anticipated Improvements Beyond Energy Impacts

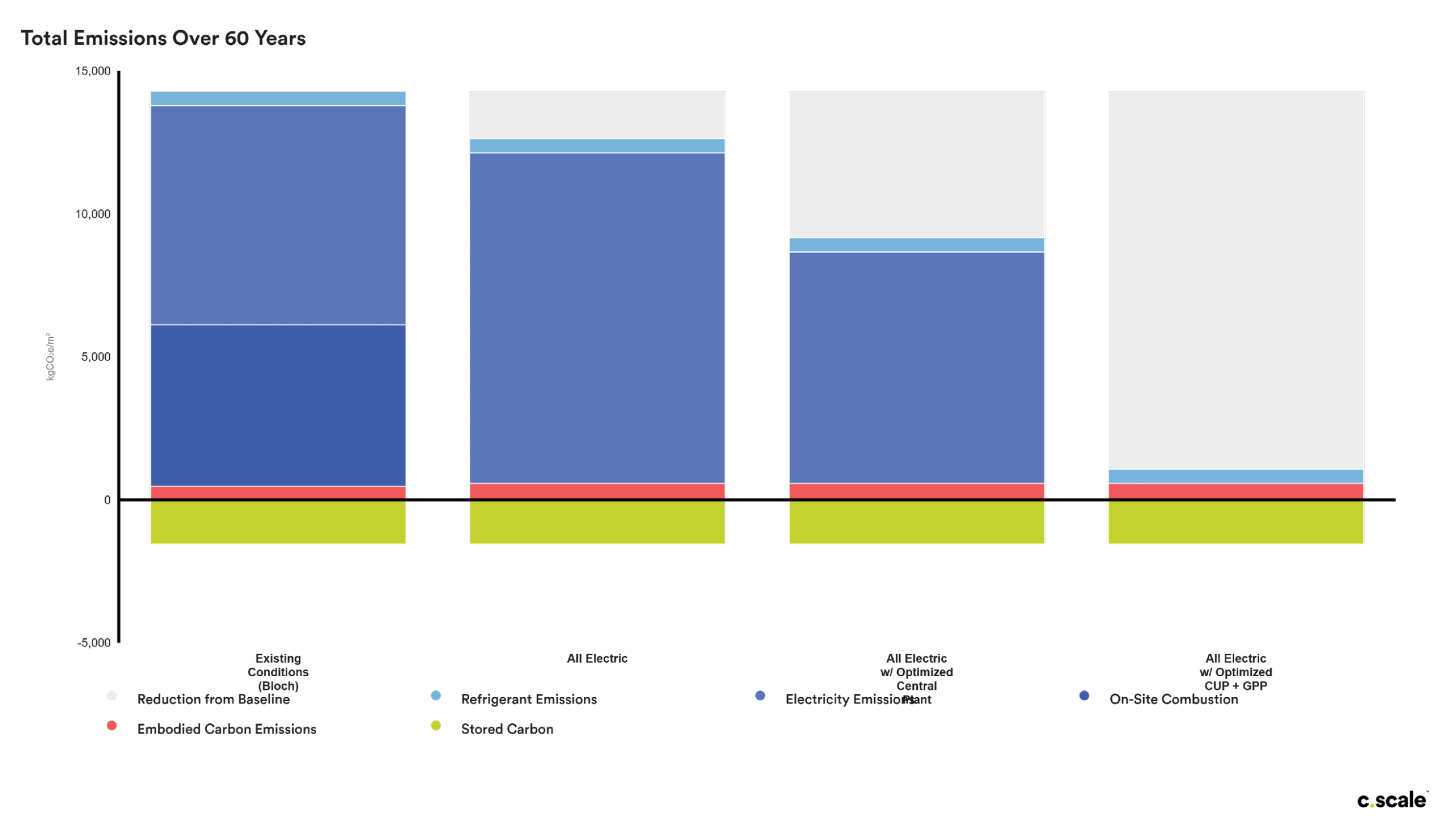

In addition to modeling energy, project analysts extended modeling to include carbon analysis over a 60-year life. The reductions included improvements in energy efficiency, not just building envelope, but also major revisions to the central utility plant. It also included runs for electrification, green power purchase from the utility, and environmentally friendly refrigerants.

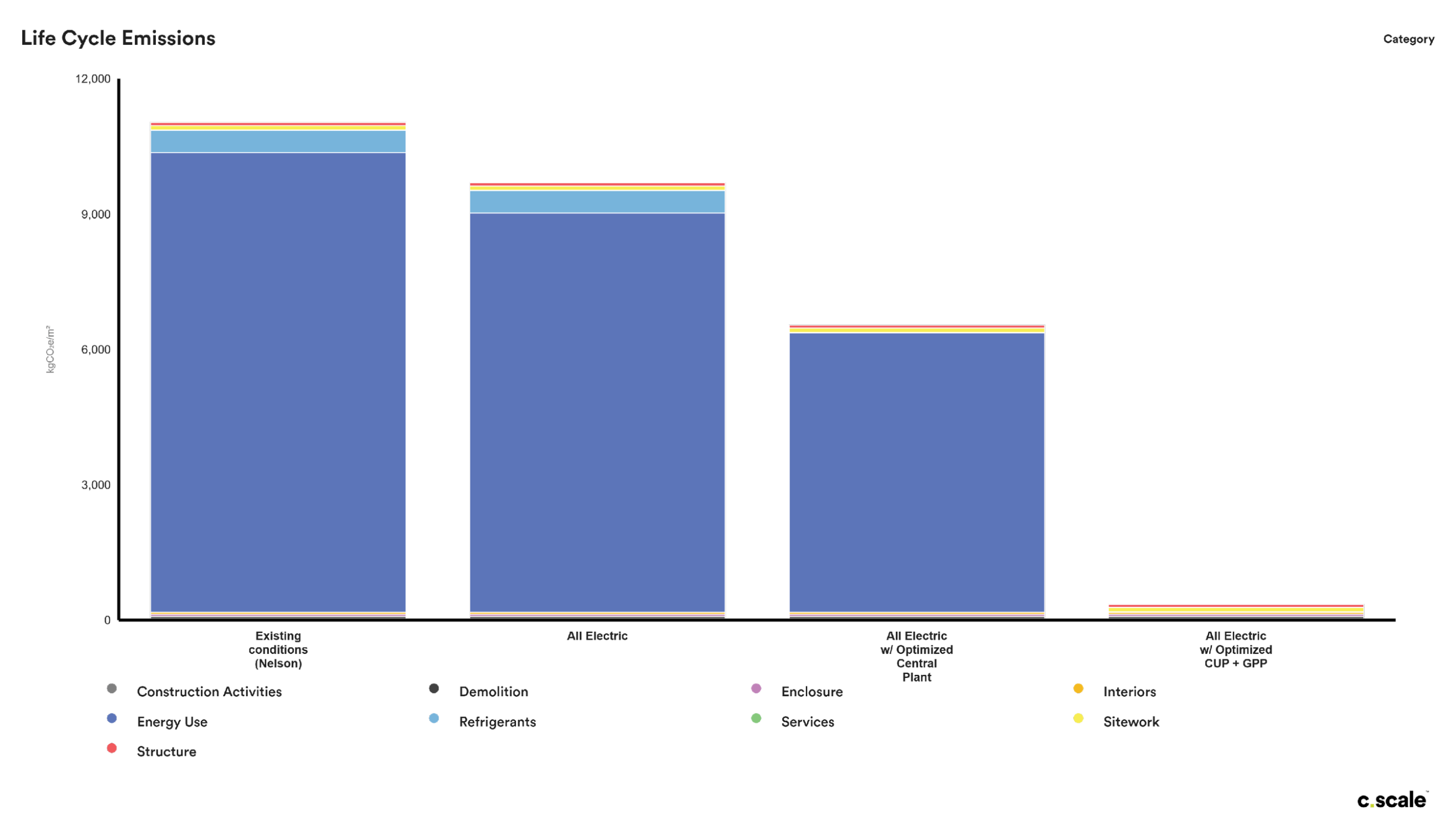

FIGURE 12 — Carbon Reduction Activities at Nelson Atkins Museum of Art – Nelson Building

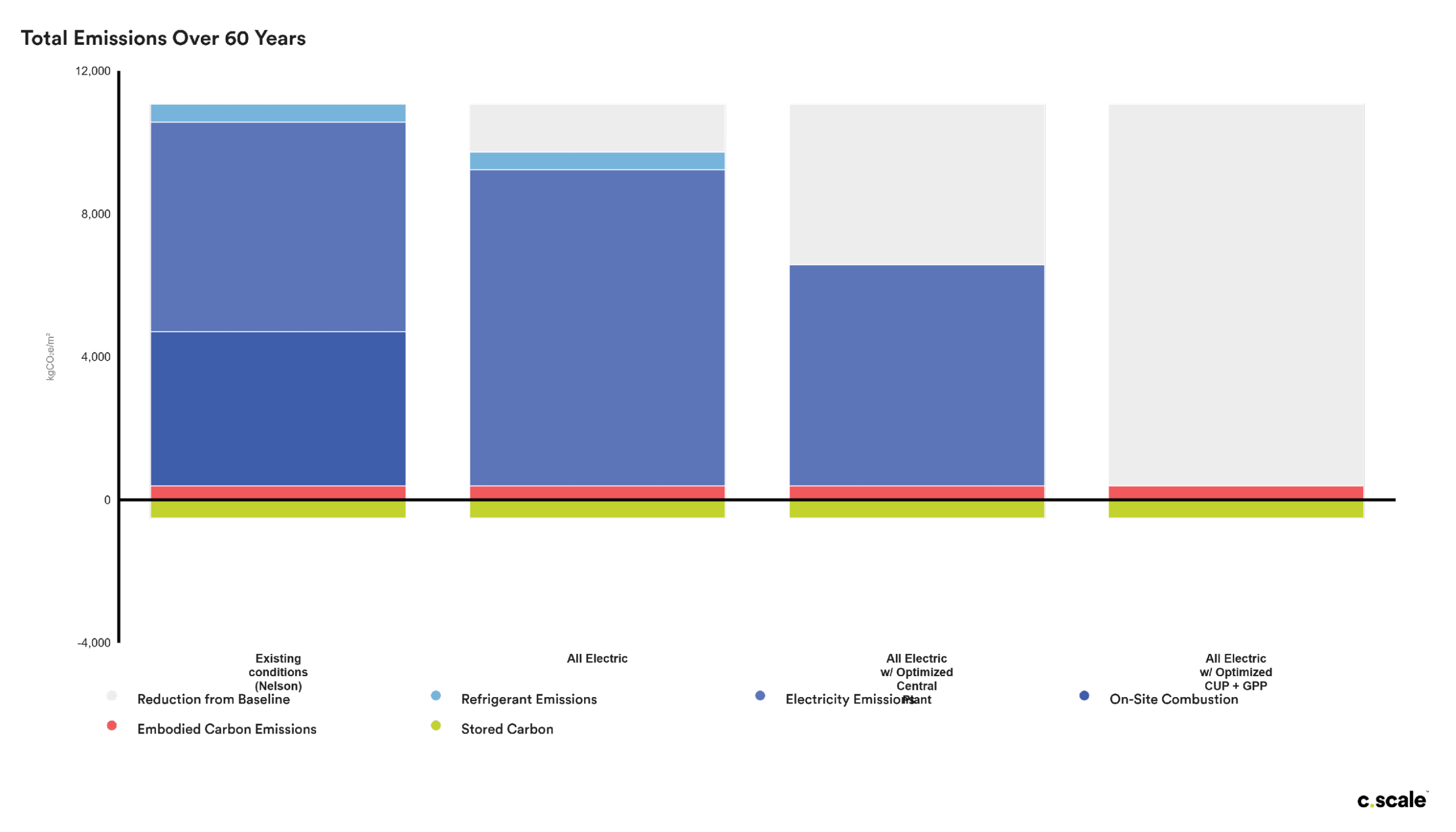

FIGURE 13 — Nelson Building Total Carbon Reductions including Sequestration

In the Nelson Atkins’ Nelson Building, a modest savings of 12% can be gained from switching from onsite fossil fuel burning (primarily for heating) to all-electric (See Figure 16 above). By optimizing the central plant, however, we can expect carbon savings ranging from 30% to as high as 75%. Modeled above is a moderate 30% savings. Regardless, if the Nelson chooses to offset with a green power purchase, then an impressive 96% of carbon is reduced.

Like Linda Hall Library, the Nelson also has a large site with many high carbon sequestering plants. But unlike Linda Hall Library, the Bloch building has a much higher Energy Use Intensity. Only after the green power purchase, then, can the Nelson fully offset its carbon footprint. See Figure 17 above.

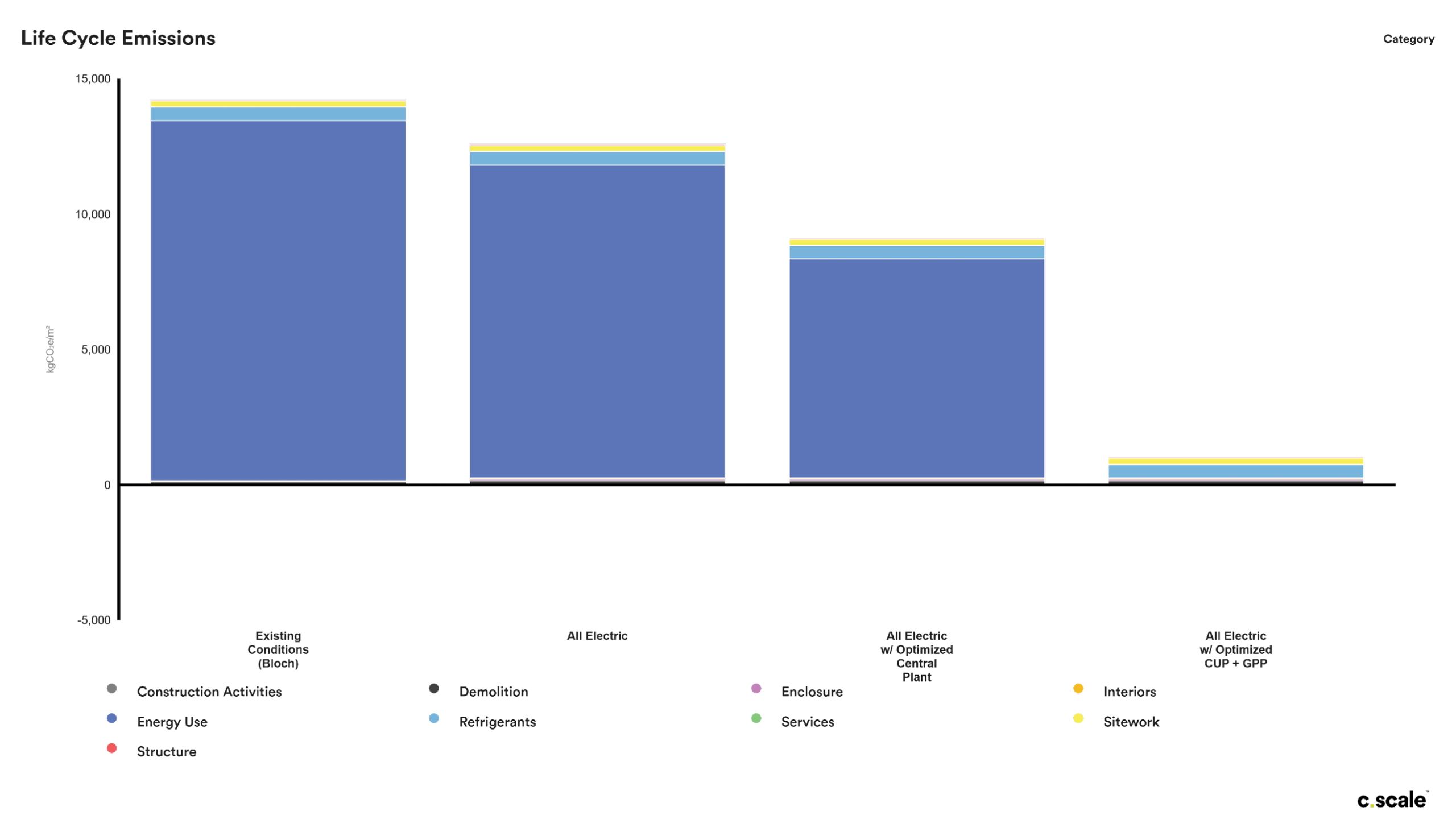

We find similar results for the legacy Bloch building. See Figures 18 & 19 below.

FIGURE 14 — Carbon Reduction Activities at Nelson Atkins Museum of Art – Block Building

FIGURE 15 — Bloch Building Total Carbon Reductions including Sequestration

TABLE 17 — Summary of Energy and Carbon Impacts for All Buildings

| Building | Baseline EUI | Envelope FIMs Tested (high level) | Level of Impact | Notes / Co-benefits |

| Linda Hall Library (LHL) | EUI 76.0 kBtu/sf/yr | Roof performance improvements; curtain wall + glazing upgrades; opaque above-grade + foundation insulation | Yes — meaningful, especially as part of a package | Biggest envelope driver is curtain wall replacement (comfort, condensation control, peak loads). Arboretum sequestration becomes a major story once operational emissions are reduced. |

| NAMA – Nelson Building | EUI 257.6 kBtu/sf/yr | Roof insulation + reflectance; selective glazing upgrades (low-e/secondary); airtightness at doors/penetrations; interior-friendly foundation + wall insulation | Moderate on energy; High on resilience/ collections protection | Envelope work likely supports lower peaks, better perimeter stability, and reduced moisture risk—but the biggest decarb lever is plant strategy + electricity procurement. |

| NAMA – Bloch Building | EUI 336.6 kBtu/sf/yr | Roof insulation + high reflectance; curtain wall upgrades (low-e or electrochromic); surface-applied low-e; infiltration sealing at interfaces/ penetrations | Yes — envelope is a primary driver | For a glass-heavy, lightweight building, glazing/shading choices often dominate cooling load, comfort, glare, and condensation behavior (and therefore HVAC sizing/operation). |

Implementation Strategy & Roadmap

Phased Implementation Plan

A. Prioritization of FIMs Based on Cost, Impact, and Feasibility

Envelope improvements are most successful when sequenced to (1) reduce risk, (2) capture the largest performance gains early, and (3) align work with planned capital cycles. Across the three buildings studied, modeling and field observations point to a consistent priority order: air leakage reduction and interface detailing provide the largest “needle-moving” opportunity, while roof insulation, slab/foundation insulation, and cool-roof measures tend to offer incremental energy savings but can still deliver important durability and comfort benefits.

TABLE 18 — Pragmatic Roadmap of Improvement Priorities

| Tier / Phase | Timing | Primary Goal | Typical Envelope FIMs in this Phase | Why it Comes First (Value) |

| Tier 1: High-Impact, High-Feasibility | 0–24 months | Reduce risk and capture the biggest “needle movers” fast | Airtightness & infiltration reduction (doors, vestibules, penetrations, transitions); water management (flashing, drainage, perimeter grading, leak repairs); targeted window tune-ups (sealants, hardware, localized condensation hotspots) | Largest modeled energy impact (air leakage) + immediate comfort and moisture-risk improvements |

| Tier 2: Strategic System Upgrades | 2–5 years | Coordinate upgrades with planned capital cycles | Glazing upgrades where overheating/solar gain is a driver (curtain wall/high exposure areas); roof insulation + membrane renewal bundled with reroofing; selective foundation-edge insulation aligned with site drainage/waterproofing work | Best cost-effectiveness when bundled with renewals; improves thermal stability and durability |

| Tier 3: Transformational Envelope Projects | 5–10 years | Deep retrofit and modernization aligned with long-range planning | Curtain wall replacement (where justified); deep insulation strategies for opaque walls (interior/exterior depending on preservation constraints); integrated façade modernization tied to broader decarbonization | Highest disruption/capital; best timed with major renovations and preservation approvals |

This phased structure supports a “build once, build wisely” approach: address leakage and moisture risks first, then pursue larger envelope upgrades in tandem with planned roof and façade renewals, and finally align deep retrofits with long-range carbon and preservation goals.

B. Coordination with Preservation Requirements for Historic Structures

For historically significant buildings, envelope performance improvements must be balanced with architectural integrity and conservation best practices. The recommended approach is to use a preservation-first decision framework:

- Prioritize reversible interventions (e.g., improved air sealing, interior secondary glazing, targeted storm windows, minimally invasive insulation strategies).

- Use mock-ups and pilot areas to validate appearance, condensation performance, and constructability before expanding scope.

- Document existing conditions and character-defining elements early, so energy upgrades are guided by an agreed preservation strategy rather than discovered conflicts during construction.

- When large envelope work is required, align improvements with periods of planned renewal (reroofing, façade restoration campaigns) so performance upgrades occur as part of a historically appropriate restoration scope.

Funding & Incentive Opportunities

A. Available Grants, Tax Credits, and Sustainability Funding Sources

A blended funding strategy is typically most successful—combining institutional capital, philanthropy, available rebates, and project-specific incentives. Potential funding pathways include:

- Utility and energy-efficiency incentives: rebates for building controls, HVAC integration measures that reduce loads, and in some cases envelope-related improvements (programs vary by utility and year).

- Public and philanthropic grants: sustainability, resilience, cultural preservation, and climate adaptation grant programs that support planning and implementation—especially when projects emphasize collection protection, risk reduction, and public benefit.

- Federal incentives for clean energy and efficiency: certain projects may qualify through tax-credit structures or nonprofit “direct pay/elective pay” approaches depending on project scope and ownership structure. (Note: Although some incentives like solar ITC Direct Pay are being phased out in 2026, many other incentives like for thermal energy systems and ground-source heat pumps remain.)

- Specialized financing: options such as performance contracting, property assessed clean energy or PACE (available in most states), low-interest sustainability funds, green loans, or other mechanisms that support lifecycle cost-effective improvements.

Because incentive programs and eligibility rules change over time, the recommended action is to develop a funding matrix during early implementation planning that maps each high-priority FIM to possible funding sources, timing windows, and documentation requirements.

Monitoring & Verification

A. Performance Tracking Post-Implementation

To ensure envelope improvements deliver real outcomes—not just modeled benefits—each project should include a monitoring and verification (M&V) plan. At a minimum, tracking should include:

- Utility tracking and normalization: monthly energy tracking with weather normalization to confirm year-over-year performance.

- Targeted envelope testing: blower door testing (whole-building or zone-based where feasible), infrared thermography under suitable conditions, and periodic inspection of repaired interfaces.

- Indoor environment tracking: perimeter temperature stability, relative humidity variability, and condensation event tracking in sensitive zones — especially relevant for collections and occupant wellness.

B. Ongoing Adjustments Based on Data Insights

Envelope performance is interconnected with operations. The M&V plan should be structured as a feedback loop:

- Use early results to fine-tune door hardware, controls sequences, humidity strategies, and maintenance plans.

- Establish thresholds and triggers (e.g., recurring condensation, persistent hot/cold complaints, unusual energy spikes) that prompt investigation.

- Maintain a living “envelope log” so recurring issues (leaks, sealant failures, seasonal discomfort) can be addressed proactively rather than episodically.

If You Can Only Do Three Things…

If you have short windows and/or tight budgets, consider these strategies first.

- Tighten the building (air sealing at doors, joints, and penetrations) to reduce energy waste and stabilize indoor conditions.

- Keep water out (roof drainage, flashing, and perimeter drainage improvements) to prevent the most costly and damaging failures.

- Fix the worst glass first (targeted glazing and shading upgrades at the most exposed façades) to reduce overheating, condensation risk, and collection stress.