Understanding and documenting the Library’s mechanical, electrical, water, and geothermal systems.

The Library’s systems are robust, but many components require updated documentation and performance verification. The geothermal well field, domestic water system, heat recovery chiller, and air handling units are key priorities.

Sections:

- Existing Mechanical, Plumbing, and Fire Protection Systems

- Existing Electrical, Lighting and Fire Alarm Systems

Key opportunities included:

- Completing a full one-line diagram set for mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems

- Reviewing geothermal performance compared to installation baselines

- Evaluating the malfunctioning heat recovery chiller and fluid cooler

- Mapping air filtration, purification, and sensing systems

- Establishing a utility data tracking workflow with repeatable metrics

These steps form the basis of a repeatable building systems assessment method that can be used annually or ahead of major planning cycles.

Summary of Electrical, Lighting and Fire Alarm System

As part of the NEH grant supporting building-wide infrastructure improvements, we conducted a thorough assessment of the electrical, lighting, and fire alarm systems at the Linda Hall Public Library. Our evaluation documents the current condition, capabilities, and limitations of these systems, providing a clear picture of existing operations.

Based on this assessment, we developed recommendations for system upgrades and modernization. These recommendations focus on replacing outdated or inefficient components, addressing code compliance, and reducing ongoing maintenance challenges. Additionally, we identified opportunities to enhance system performance, improve day-to-day operations, and create a more robust and future-ready infrastructure. Implementing these improvements will help ensure the Library’s systems are reliable, efficient, and capable of supporting long-term facility needs.

Existing Electrical, Lighting and Fire Alarm Systems

TABLE 1 — Existing Systems Summary (2025)

This table summarizes the library’s major building systems. More detailed technical descriptions are available below for readers who want deeper insight.

| What’s in place today | What that means in plain language | |

| **Utility power (incoming service)** | One utility feed at **13.2 kV** feeding two transformers | The campus relies on a **single utility source** (no redundant utility feed), then steps power down for building use |

| **Transformers (power “step-down”)** | **500 kVA** transformer to **208/120V** and **750 kVA** transformer to **480/277V** | Two “levels” of electricity are used: **standard building power** (208/120V) and **higher-capacity power** (480/277V) for larger equipment |

| **Electrical distribution** | Bus ducts and switchboards distributing power across the campus (includes main boards and building buses) | Power distribution is robust but **complex**, with multiple pathways feeding different building areas and equipment rooms |

| **Backup power (generators)** | Two standby generators: **40 kW (208/120V)** for limited emergency loads; **250 kW (480/277V)** for selected standby/optional loads (currently underutilized) | The campus has backup power, but it is **selective**—it supports specific panels/loads rather than full-building backup |

| **Interior lighting** | Mostly older **fluorescent** fixtures; expansion areas have early occupancy sensors; manual wall switches | Lighting works, but it’s largely **older technology** with **limited automation**, inconsistent performance, and higher maintenance burden |

| **Emergency egress lighting** | Battery packs built into individual fixtures | Emergency lighting is **decentralized**—each fixture has its own battery, which can increase maintenance checks and replacements |

| **Fire alarm** | **Simplex addressable** fire alarm system campus-wide; mostly photoelectric smoke detectors in corridors/utility spaces | A solid baseline system, but smoke detection coverage is **strongest in hallways and support spaces**, with **limited coverage** elsewhere |

| **Very early smoke detection (VESDA)** | **None currently** | There is no “ultra-early” smoke detection system designed to protect high-value collections before smoke becomes visible |

TABLE 2 — Recommended Improvements Summary

This table summarizes the library’s major building systems. More detailed technical descriptions are available below for readers who want deeper insight.

| Recommendation | What it is (plain language) | Primary benefit |

| **Upgrade fire alarm system** | Update to a modern fire alarm platform with improved coverage, smarter detection, and better monitoring | Better life safety, fewer nuisance alarms, more reliable diagnostics, and easier future expansion |

| **Add VESDA for collections protection** | Install an “early warning” air-sampling smoke detection system in key library/archival areas | Detects smoke **much earlier**, helping protect collections and reduce damage from fire or sprinkler activation |

| **LED lighting retrofit** | Replace aging fluorescent fixtures with modern LED lighting | Lower energy use, improved lighting quality, and reduced maintenance |

| **Modern lighting controls** | Add code-compliant controls such as occupancy/vacancy sensing, scheduling, daylight dimming, and zoning | More comfort and flexibility, measurable energy savings, easier operations |

| **Microgrid readiness (future option)** | Plan for on-site energy + controls so the building can operate more independently during outages | Improved resilience and sustainability; foundation for future energy strategy |

| **Rooftop solar (concept)** | Preliminary rooftop PV estimated at **~211 kW** | Meaningful reduction in utility use during daytime, though not enough for full campus demand |

| **Resilience generator strategy (concept)** | Proposed **500 kW** generator for 208/120V loads and **750 kW** for 480/277V loads | Stronger backup capability aligned with existing transformer “size” and campus load priorities |

| **Submetering** | Add electrical meters on major loads and generator-backed circuits | Better visibility into where energy is used, improved planning, and better verification of emergency power capacity |

The facility is served by a single utility electrical service at 13.2 kV, which terminates at a utility-owned medium-voltage switch. This switch distributes power to two pad-mounted transformers. The first transformer is rated at 500 kVA with a 13.2 kV primary and a 208Y/120V secondary. The second transformer is rated at 750 kVA with a 13.2 kV primary and a 480Y/277V secondary.

The 500 kVA, 208Y/120V transformer supplies multiple downstream distribution systems, including two 1,600 A bus ducts, one 800 A bus duct, and a 400 A distribution panel (DP). Of the two 1,600 A bus ducts, one feeds the 1,600 A Main Distribution Switchboard (MDP), while the second feeds a separate 1,600 A switchboard designated as Panel “P.” The 800 A bus duct functions as the west building main bus and primarily serves electrical panels located within the elevator machine rooms.

The electrical infrastructure also includes two onsite standby generators. A 40 kW, 208Y/120V generator provides emergency power to a 100 A emergency panel (BPP), supporting designated 208Y/120V standby loads. In addition, a 250 kW, 480Y/277V generator supplies a 400 A distribution board (DMPA) serving selected 480Y/277V standby and optional loads.

Interior lighting within the main building primarily consists of legacy fluorescent luminaires controlled via local toggle on/off switches. Areas within the building expansion incorporate early-generation occupancy sensing technology, which is routed through a centralized lighting contactor panel in conjunction with local manual switching. Emergency egress lighting is provided by integral emergency battery packs located within individual luminaires.

The fire alarm system is a Simplex addressable system serving the entire campus. Fire alarm devices are distributed throughout the facility and primarily include photoelectric smoke detectors as the main method of smoke detection, along with associated fire/smoke dampers. Smoke detectors are predominantly installed within corridors, hallways, and utility spaces.

At present, the campus does not include Very Early Smoke Detection Apparatus (VESDA) or other aspirating smoke detection systems.

Replacement Recommendations

Fire Alarm System Replacement

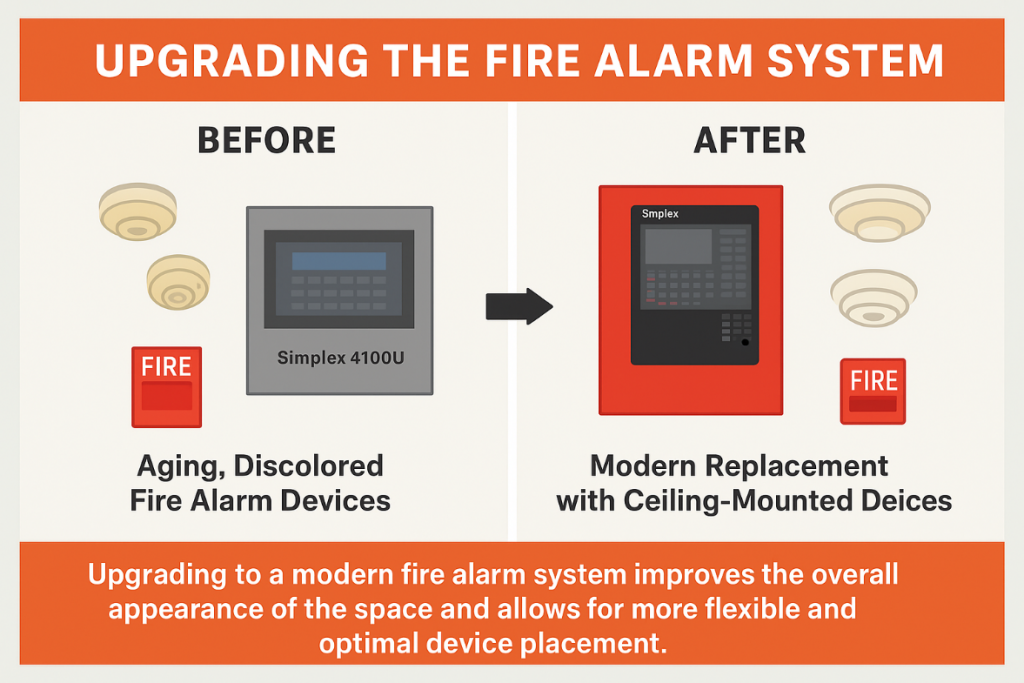

The existing fire alarm system is a Simplex addressable system serving the entire campus. Fire alarm initiating and notification devices are distributed throughout the facility and primarily consist of photoelectric smoke detectors, which serve as the primary means of smoke detection, along with associated fire and smoke damper controls. Currently, smoke detection is predominantly provided within corridors, hallways, and utility spaces, with limited coverage in other occupied or critical areas.

It is recommended that the facility upgrade to a modern Simplex fire alarm system that complies with current code requirements and contemporary life-safety best practices. A modern system would provide expanded smoke detection coverage throughout all required spaces, rather than being limited to corridors and utility areas, thereby improving overall life-safety performance. Upgrading the system would enhance early detection capabilities, reduce nuisance alarms through improved detection algorithms, and allow for greater system reliability and diagnostic capability. In addition, a modern fire alarm platform would support enhanced system monitoring, improved integration with other building systems, and increased flexibility for future expansions or code-driven modifications, while ensuring continued compliance with current NFPA and local authority requirements.

FIGURE 1 — Fire Alarm Upgrade

VESDA System Inclusion

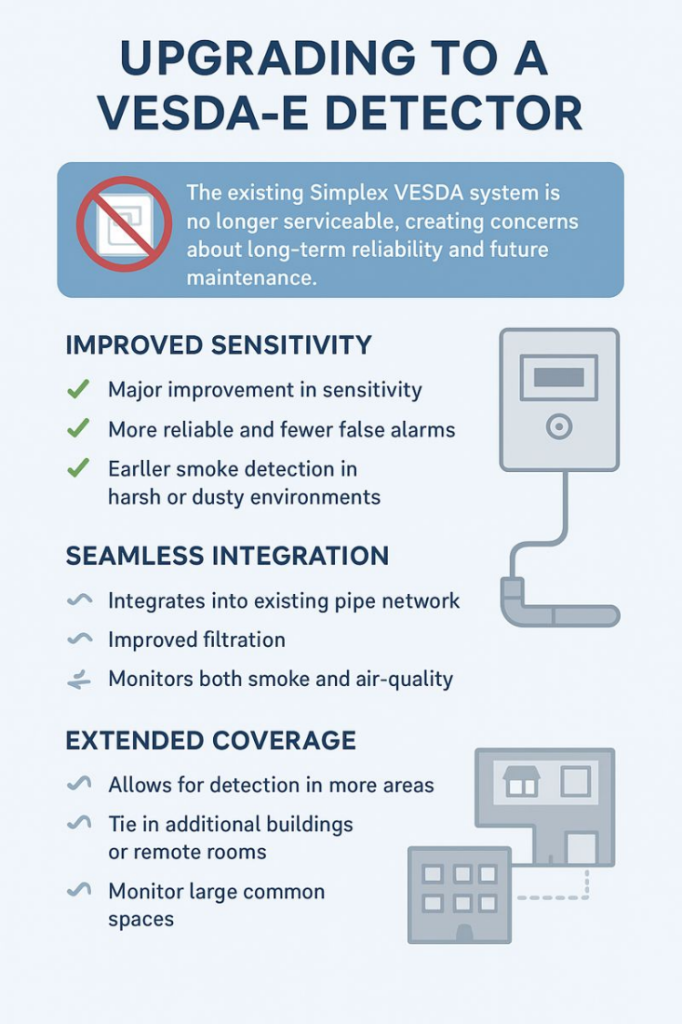

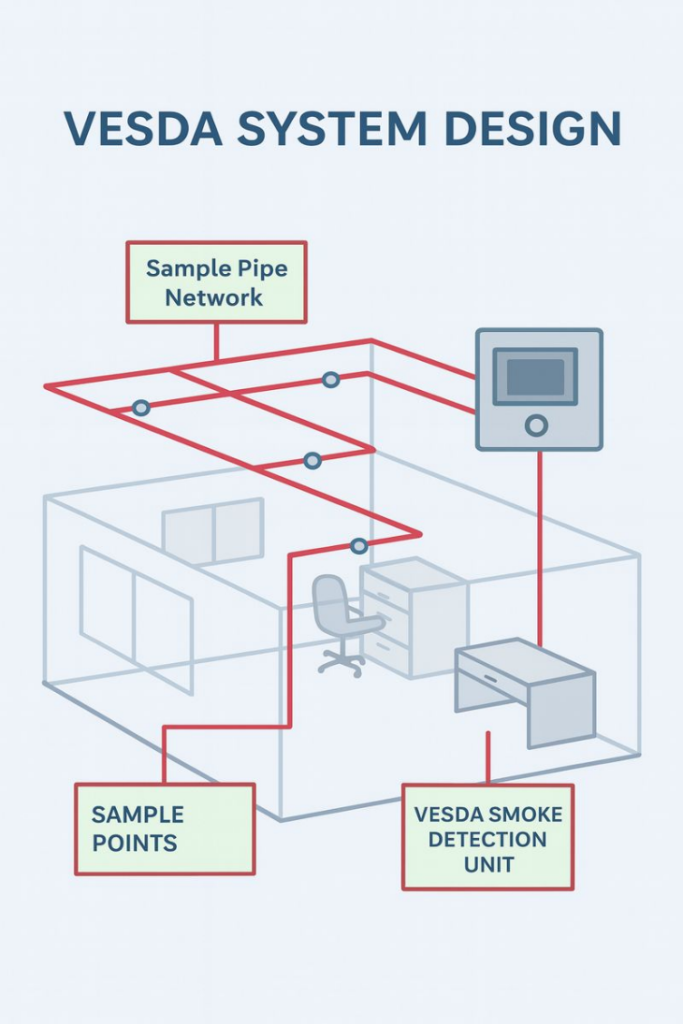

At present, the campus does not include Very Early Smoke Detection Apparatus (VESDA) or other aspirating smoke detection systems.

Libraries are well-suited for Very Early Smoke Detection Apparatus (VESDA) systems due to the high fire load associated with books, archival materials, and other irreplaceable collections, as well as the need to minimize damage from both fire and fire-suppression activities. A VESDA system provides extremely early detection of smoke at the incipient stage, often before visible smoke or heat is present, allowing staff to investigate and address potential issues before a fire develops. This early warning capability helps protect valuable collections, reduces the likelihood of water damage from sprinkler activation, and supports continued building occupancy and operations with minimal disruption. VESDA systems are particularly effective in libraries because they can provide reliable detection in large open reading rooms, stacks, special collections areas, and concealed spaces, while remaining discreet and minimally intrusive to historic or architecturally sensitive environments.

An example of a suitable VESDA system for a library is the Xtralis VESDA-E VEA or VESDA-E VLP aspirating smoke detection system. These systems use high-sensitivity laser-based detection and a network of small-diameter sampling pipes to continuously monitor air quality across protected spaces. The VESDA-E series offers multiple programmable alarm thresholds, advanced airflow monitoring, and seamless integration with modern addressable fire alarm systems, making it well-suited for protecting library collections, reading areas, and archival storage while meeting current life-safety and asset-protection objectives.

FIGURE 2 & 3 — VESDA System Upgrade

Lighting Systems

Interior lighting within the main building primarily consists of legacy fluorescent luminaires controlled by local toggle on/off switches, offering limited functionality and minimal energy management capability. Areas within the building expansion incorporate early-generation occupancy sensing technology that is routed through a centralized lighting contactor panel in combination with local manual switching. While functional, this approach reflects outdated control strategies and provides limited flexibility for zoning, scheduling, or energy optimization. Emergency egress illumination is currently provided by integral emergency battery packs within individual luminaires.

It is recommended that all interior lighting be upgraded to modern LED luminaires to improve energy efficiency, reliability, and overall lighting performance. Much of the existing lighting exhibits visible signs of aging, including discoloration and reduced output, and replacement with LED fixtures would provide a cleaner, more contemporary appearance while significantly reducing energy consumption and maintenance requirements. LED lighting also offers improved light quality, longer service life, and better compatibility with advanced control systems.

In addition, it is recommended that the lighting control system be upgraded to a modern, code-compliant lighting control platform. Contemporary lighting control technologies provide enhanced functionality, including occupancy and vacancy sensing, daylight harvesting, time scheduling, and improved zoning and scene control. These systems support compliance with current energy codes while offering greater operational flexibility, improved occupant comfort, and measurable reductions in lighting energy use.

Other System Improvements

System Wide Microgrid Solution

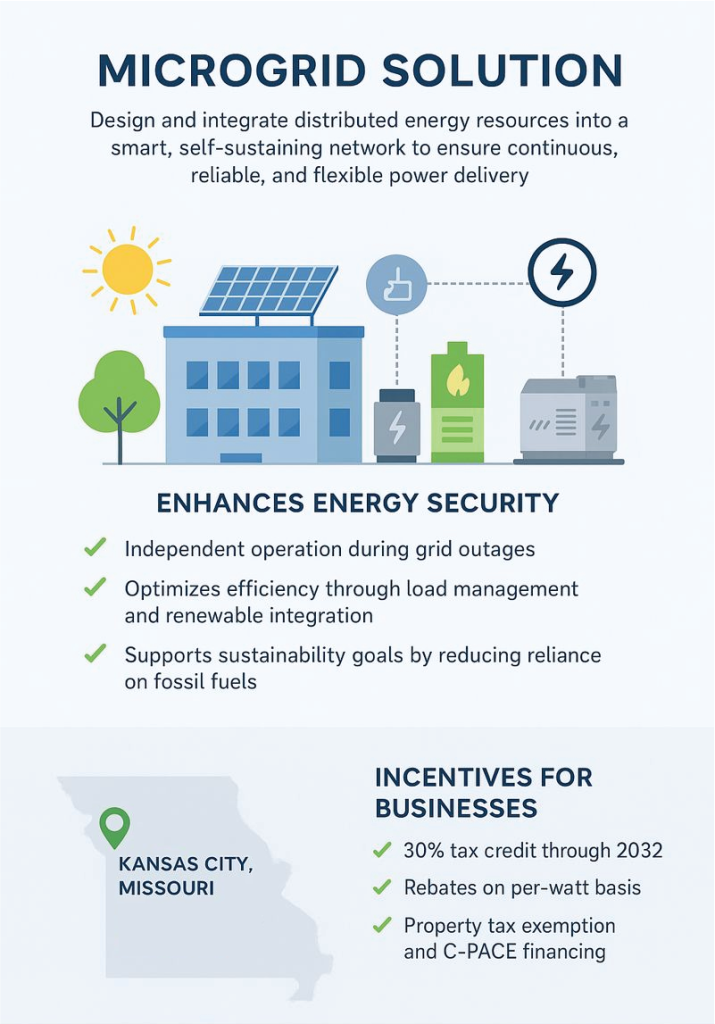

Implementing a microgrid solution to provide holistic resiliency to the building-wide electrical system involves designing and integrating distributed energy resources (such as solar PV, Fuel Cell, battery storage, and backup generation) into a smart, self-sustaining network. This approach enhances energy security by enabling the building to operate independently during grid outages, optimizes efficiency through load management and renewable integration, and supports sustainability goals by reducing reliance on fossil fuels. The microgrid ensures continuous, reliable, and flexible power delivery while creating a future-ready infrastructure that safeguards occupants, operations, and critical systems.

A preliminary photovoltaic (PV) system layout was developed to evaluate the facility’s potential for on-site solar power generation utilizing the available roof areas. Based on this initial assessment, the combined installed capacity of the rooftop PV system is estimated at approximately 211 kW.

For reference, the August 2025 Evergy utility bill indicates a peak facility demand of approximately 499 kW. While the proposed on-site solar installation would not be sufficient to fully support the facility’s total electrical demand, it would meaningfully reduce the facility’s reliance on utility-supplied power and contribute to overall demand reduction during daylight hours.

Achieving full independence from the utility grid would require additional generation capacity beyond what is available on the existing roof areas. This could potentially be accomplished through supplemental off-site solar generation or other renewable energy sources, in combination with appropriate interconnection, energy storage, and load management strategies.

To provide a campus-wide backup power solution, the proposed design includes the installation of a s 500 kW standby generator for the 208Y/120V loads and a 750kW generator for the 480Y/277V loads. These generators’ capacities are anticipated to be sufficient to support the campus’s critical and essential electrical loads during utility outages. The selected generator size aligns closely with the capacity of the existing 500 kVA and 750kVA utility transformers, providing consistency with the current electrical infrastructure and facilitating integration into the existing distribution system.

A potential system interconnection point for either microgrid solution has been identified and shown on the one-line diagram.

Businesses in Kansas City, Missouri can take advantage of a strong mix of federal, state, utility, and local incentives to reduce the cost of commercial solar projects. At the federal level, the Investment Tax Credit (ITC) provides a 30% tax credit on system costs through 2032, while MACRS accelerated depreciation allows businesses to recover much of the investment within the first few years. Missouri further supports solar adoption with a property tax exemption that excludes added system value from assessments and net metering through Evergy, which credits excess electricity generation back to utility bills. Evergy also offers rebates on a per-watt basis, helping reduce upfront installation costs. Kansas City bolsters adoption through the Kansas City Energy Project, which provides technical assistance, and streamlined permitting for solar systems. For financing, commercial property owners can use C-PACE (Commercial Property Assessed Clean Energy) to cover up to 100% of project costs with long-term, property-tax-based repayment, ensuring positive cash flow without upfront capital. Together, these grants, tax credits, rebates, and financing mechanisms create a comprehensive pathway for KCMO businesses to pursue sustainable, cost-effective solar energy.

FIGURE 4 — System Wide Microgrid Solution

Submetering

We recommend installing electrical submetering, as indicated on the one-line diagrams, to provide detailed monitoring of major facility loads as well as all loads connected to the generator. Submetering would give the facility the ability to track energy usage by building area or system type, identify high-demand equipment, and better understand how power is distributed throughout the campus. It would also allow staff to monitor generator-connected loads more accurately, helping assess real emergency load demand, verify capacity, and support operational planning. Overall, adding submeters creates a clearer picture of how the electrical system performs, enabling more informed decisions regarding energy management, maintenance, and future infrastructure improvements.

Conclusion

The comprehensive evaluation of the Linda Hall Public Library’s electrical, lighting, and fire alarm systems highlights both the strengths and limitations of the current infrastructure. While the existing systems provide basic functionality, several components are aging, inefficient, or limited in capability, presenting opportunities for modernization and improved performance.

The recommended upgrades — including fire alarm replacement, VESDA system implementation, LED lighting and controls, microgrid integration, and electrical submetering — collectively aim to enhance safety, operational efficiency, and system resilience. By adopting these improvements, the Library can achieve a more reliable, energy-efficient, and future-ready infrastructure that supports both day-to-day operations and long-term strategic goals.

Implementing these measures will not only ensure compliance with current codes and best practices but also protect valuable library collections, improve occupant safety and comfort, and provide a scalable platform for future technological enhancements. In sum, the proposed improvements position the Linda Hall Public Library to operate with greater efficiency, reliability, and adaptability well into the future.

Existing Mechanical, Plumbing, and Fire Protection Systems

FIGURE 5 — Existing Facility Systems Map

The facility is comprised of three buildings. The main building was built around 1956. The South addition to the main building was added around 1976. The History of science center was added around 1965. The Library was completed when South building was added around 2005. With each expansion, the cooling and heating systems have been modified.

The most current chilled water system provides 350 tons of cooling from heat pumps supplemented by a fluid cooler and a chiller. The heat pumps are located in the southwest mechanical room of the History of science center. The fluid cooler and chiller are located outside to the west of the History of science center. The Library uses two heating hot water boilers for heating air and hot water, and uses one steam boiler for humidification. All of these units are in the boiler room of the main building. The main building has two Mechanical Equipment Penthouses on its roof that houses most of the Library’s air handling units (AHUs). Other AHUs not in the penthouse, are either specialized equipment (Rare Book Room AHU) or were added for supplemental cooling, heating and humidification loads as the Library expanded. The roof of the main building also houses Air Cooled condensers that are no longer operational.

Of the 100,00 gallons of annual water used to irrigate, roughly 700,000 might be provided through reclaimed water providing a full offset of usage.

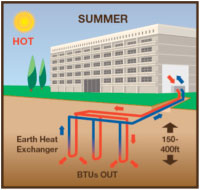

FIGURE 6 & 7 — Seasonal Geothermal Systems

Geothermal systems consist of a ground-loop system, a network of heat-transferring liquid filled pipes buried deep into the ground to harness the constant temperature below the earth’s surface. During the summer season when cooling is required, the system will take excess heat and disperse into the ground. Similarly in the winter when heat is required, heat from the ground is absorbed and returned into the space that needs to be conditioned. Geothermal systems are known for their efficiency, often performing better than traditional HVAC systems. Ground source heat pump systems offer longer and more durable equipment life due to avoiding outdoor equipment. An added environmentally conscious benefit of heat pumps is that since they don’t rely on combustion, they can reduce energy costs by up to 50% and have the capacity to produce zero direct emissions. Restoring the geothermal system to its initial design intent would remarkably improve the performance and operation of the facility. These improvements could aid the Linda Hall Library with future equipment replacements and building system modifications to further improve the efficiency, resiliency, and adaptability of the Library.

https://www.advanceair.net/geothermal-ground-source-heat-pumps/

Insulation:

From site observations, we believe that 20% of each institutions’ hydronic piping insulation is damaged. Damaged or missing piping leads to energy losses, reduced efficiency, and higher energy costs due to the system overcompensating to maintain the set temperature. Below is a summary table of operational costs due to insufficient insulation.

TABLE 3 — Insulation Annual Energy and Cost Impact

| Estimated Pipe Length (ft.) | 21000.00 |

| Estimated Damaged Pipe (%) | 20 |

| Annual Energy Loss (BTU/hr) | 31712.46105 |

| Annual kWh Lost | 947301.95 |

| Annual $ lost | 113676.23 |

Equivalent trees that would need to be planted to offset kWh loss: 220,586.3

Kwh To Co2 Calculator – Glow Calculator

Humidification and Moisture Control

The Linda Hall Library currently useS steam humidifiers for the humidification and moisture control of their building. From site observations. Although a higher upfront cost, adiabatic humidification would be recommended. Not only would this save carbon emissions and operating costs due to the decrease in steam generation, over the system’s life energy costs and water costs would also decrease due to most of the energy generation in adiabatic humidification coming from pump energy. Additionally, water could be re-used either in an RO reclaim system, or can be another source of greywater.

TABLE 4 — Total Hourly and Annual Energy, Fuel, and Cost Summary

| TOTAL | TOTAL | YEARLY | YEARLY |

| (LBS/HR) | BTUs/HR | (GALLONS) | $ |

| 3,325.00 | 3,823,750.00 | 1,644,045.59 | 18,084.50 |

| HOURLY | HOURLY | YEARLY | YEARLY |

| (KWH) | $ | KWH | $ |

| 1,131.68 | 90.53 | 3,395,026.52 | 271,602.12 |

| HOURLY | HOURLY | YEARLY | YEARLY |

| (MCF) | $ | MCF | $ |

| 5.63 | 28.16 | 22,525.77 | 109,250.00 |

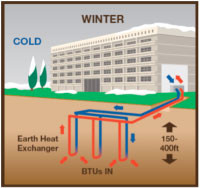

Fan Array Retrofits

The energy required for distributing heating and cooling, heat rejection, and ventilation inside a commercial building accounts for roughly 25% of the energy consumed in the United States. [1] Out of that load, 50% of the energy consumed by supply fans. [2] Multiple smaller fan array systems will also provide redundancy and resilience, for if one fan’s motor fails; the rest of the fans will increase motor power until failed fan motor is fixed. This ensures the comfortability of occupants and decreasing degradation of equipment and objects stored within the institutions. When all fans are working, they operate part load, leading to higher energy savings due to HP reduction, via fan law. Updating or retrofitting units with will accumulate to energy savings. Additionally, the local utility company has a rebate program for retrofits and upgrades that each institution can take advantage of and have even higher savings.

Energy Savings from Fan Arrays – Full Load

TABLE 5 — Fan Energy Use and Savings

| Linda Hall Library | Full Load | kWh per year |

| Fan Array HP Total | 94.2 | 615,345.57 |

| Existing HP Total | 97.01 | 633,701.42 |

| Savings Full Load | $ 2,202.70 |

FIGURE 8 — Fan Array Efficiency

Rainfall Capture

Using utility information over the past eight years, we evaluated that rainwater capture would be able to offset 100% of the Linda Hall Library’s average annual irrigation water usage. At this point in time, condensate capture from equipment would be a secondary as it is not needed for system justification.

TABLE 6 — Monthly Precipitation and Stormwater Volume

| Linda Hall | In/Month | Precipitation Days | Volume (gal) per Precipitation Month |

| Jan | 0.66 | 1.70 | 18,133.15 |

| Feb | 0.83 | 2.70 | 23,448.04 |

| March | 1.16 | 6.50 | 33,765.18 |

| April | 1.93 | 9.40 | 57,838.50 |

| May | 2.99 | 12.60 | 90,978.40 |

| June | 2.26 | 12.50 | 68,155.64 |

| July | 2.49 | 10.30 | 75,346.38 |

| Aug | 3.04 | 9.70 | 92,541.61 |

| Sept | 2.06 | 8.90 | 61,902.83 |

| Oct | 2.78 | 6.80 | 84,412.95 |

| Nov | 1.50 | 4.60 | 44,394.96 |

| Dec | 1.10 | 2.70 | 31,889.34 |

| Annual | 22.81 | 88.40 | 710,319.36 |

References:

[1] Energy Consumption Characteristics of Commercial Building HVAC Systems

[2] Air Handling Units: Energy Efficiency Measures | HVAC Resource Map